Apartment List's 2024 Millennial Homeownership Report

The Millennial identity has been shaped in large part by the housing market. The housing market’s collapse in 2008 triggered a recession just as the generation entered the workforce, and its lack of affordability today leaves many feeling priced out of the “American Dream.” For some Millennials, there is also a sharp divide between their lived experience and that of their parents, for whom an abundant housing market made homeownership – and its long-term benefits – attainable as younger adults.

That said, today Millennials are the nation’s largest generation, and by sheer volume they are purchasing more homes than any other group. The Census Bureau even credits them with driving a recent upward trend in homeownership nationwide. But despite some positive trends recently, long-term data show Millennials remain well-behind previous generations when it comes to owning homes.

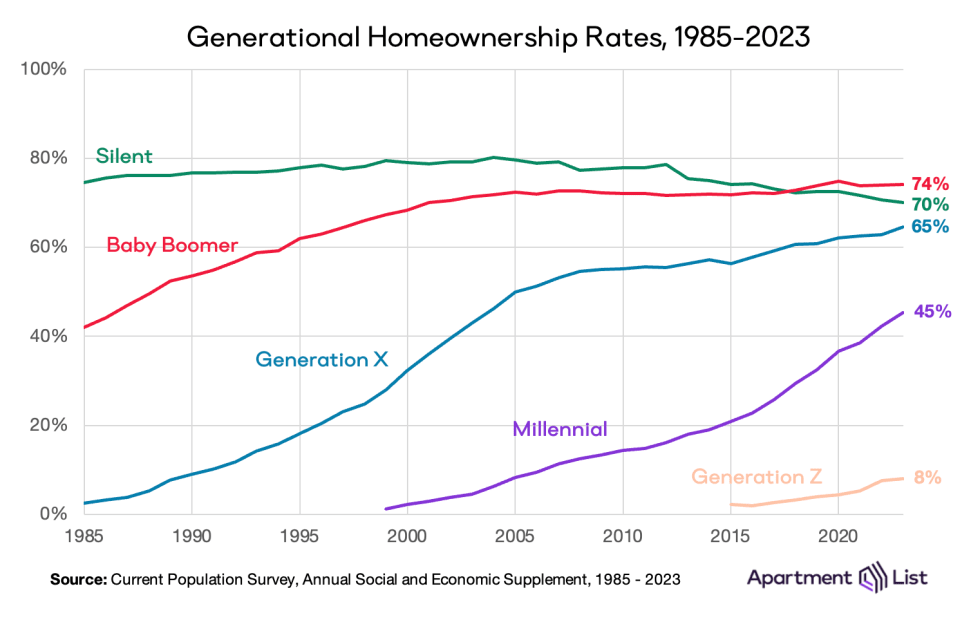

According to the latest data from Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, the Millennial homeownership rate stands at 45.5 percent in 2023. As expected, rates are higher for older generations.1 At the top are Baby Boomers, of whom 74 percent own homes. Boomers recently passed the Silent generation (70 percent) who, now in their 80s and 90s, may be selling homes to live with younger relatives or in assisted living facilities. Generation X homeownership has been trending up since 2015, reaching a high of 65 percent today. Next come Millennials (45 percent), followed by Generation Z (8 percent), the oldest of whom were just 26 in the most recent year of data.

How we measure homeownership

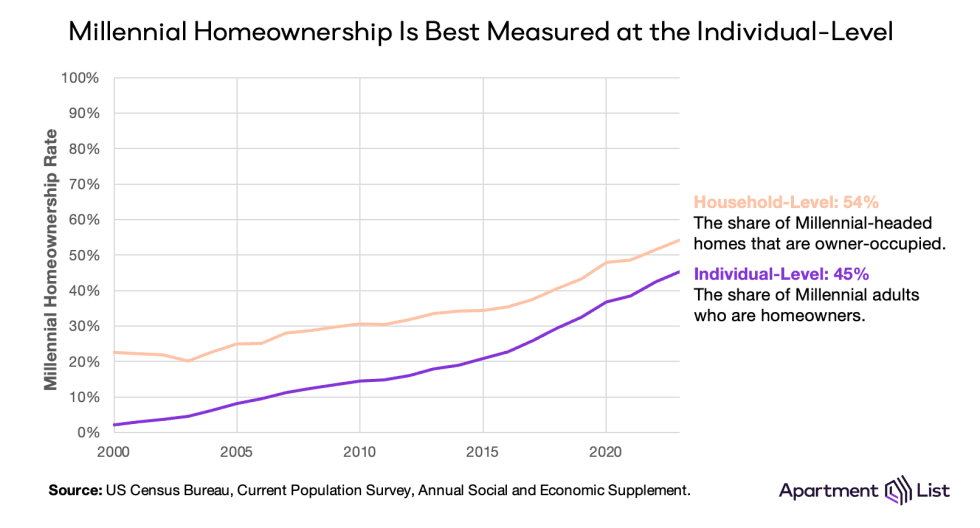

Before diving further into the data, an important methodological note: recently, our team published a comparison of the officially reported homeownership rate (i.e., the share of housing units that are owner-occupied) against an alternative calculation that measures homeownership at the individual level (i.e., the share of adults that are the householder, or the spouse of the householder, in an owner-occupied home). We found that the two measures have been diverging, and that the conventional approach may be understating the impact of affordability challenges on younger generations.

To demonstrate the nuance more clearly: consider a household that includes a married couple (who own their home) and their two adult children who live with them. Using the conventional household definition we would conclude a homeownership rate of 100 percent; there is one household and it is owner-occupied. But if we look at the individuals within the household we get a rate of just 50 percent, which feels more consistent with how we think of homeownership: as something a person attains, rather than something a household attains.

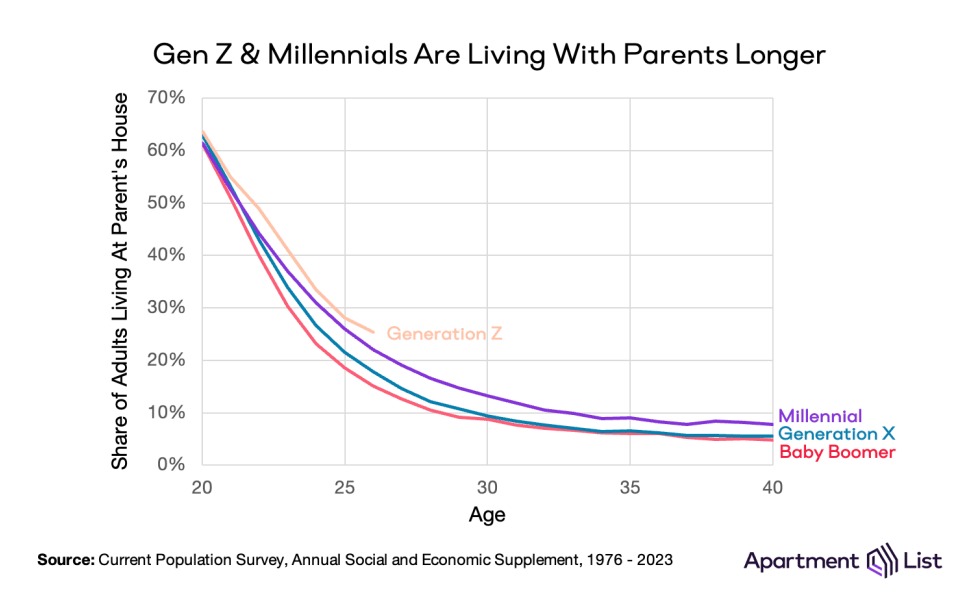

This becomes especially important when we measure homeownership for younger generations, because young adults today are waiting longer to form their own households. Instead, they’re living with family for longer, which paradoxically biases homeownership upwards when it is calculated at the household level (the orange line in the chart below). Calculating it at the individual level, on the other hand, solves this problem by identifying “young adults who rent” and “young adults who live at home” equally (the purple line).

For these reasons, we present individual-level homeownership rates in this report.

Millennial homeownership is growing slower than previous generations

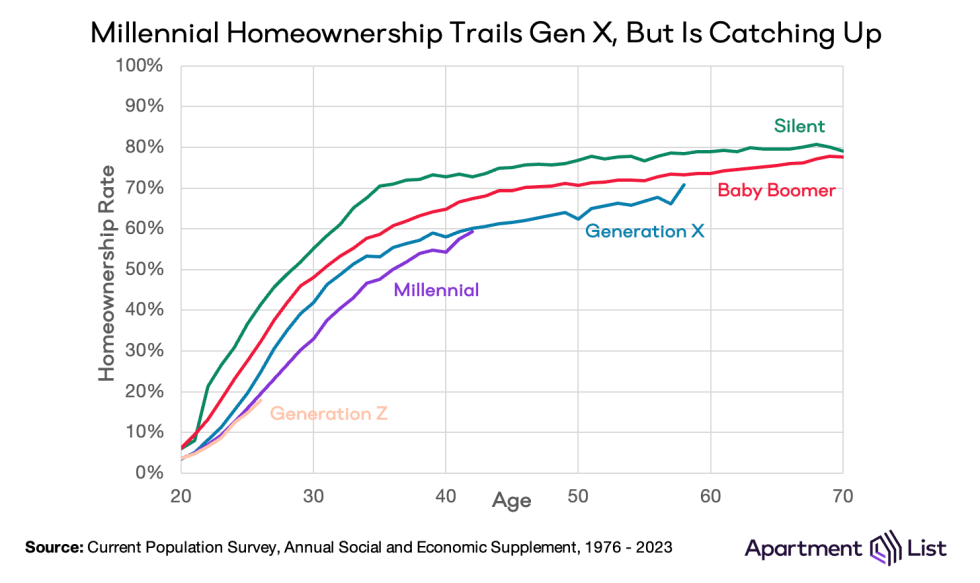

With the new definition in mind, we can make an even stronger comparison across generations by controlling for age and calculating homeownership within equal stages of life. While Millennials have developed a somewhat unique reputation for struggling in the housing market, they’re actually the third consecutive generation to purchase homes slower than those who preceded them. By age 30, 55 percent of Silents owned homes, compared to 48 percent of Boomers, 42 of Gen Xers, and just 33 percent of Millennials.

Low Millennial homeownership by age 30 was largely driven by the Great Recession, which suppressed the U.S. economy just as many Millennials were reaching adulthood, graduating college, and trying to get their professional careers off the ground. Furthermore, the recession spurred a dramatic shift in new housing construction: less investment in suburban, single-family homes and more in urban, multi-family apartments. So when the economy recovered, and many Millennials were drawn to jobs in centrally-located cities, some found that renting apartments made more financial sense than buying starter homes that were becoming increasingly scarce and expensive.

The Great Recession affected Generation X as well, who at the time were in their 30s and 40s. Generation X purchased many homes in the bubble period before the recession, so their homeownership rate slowed noticeably when many of those mortgages became foreclosures. As a result, we see Millennial homeownership catching up to Generation X by age 40, but making up little ground to earlier generations.

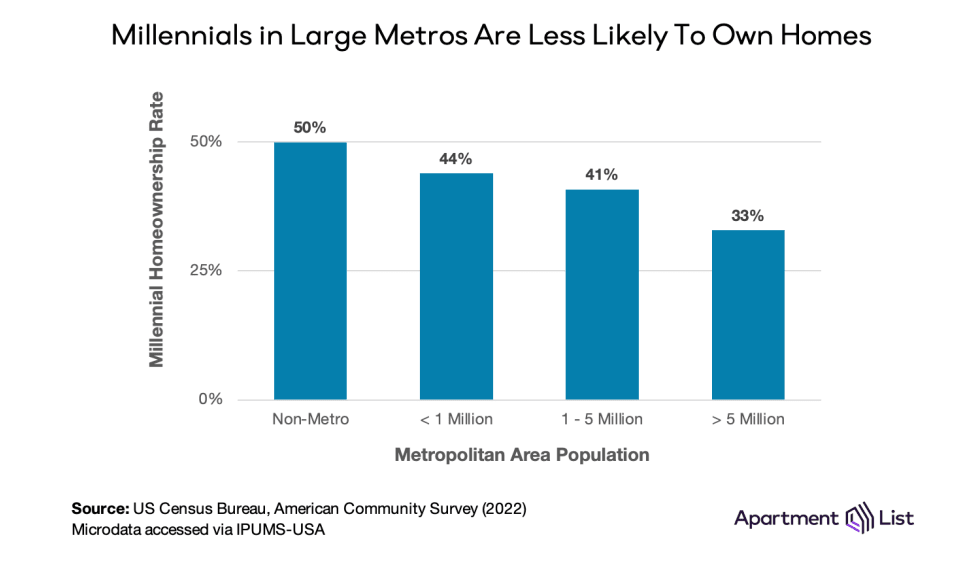

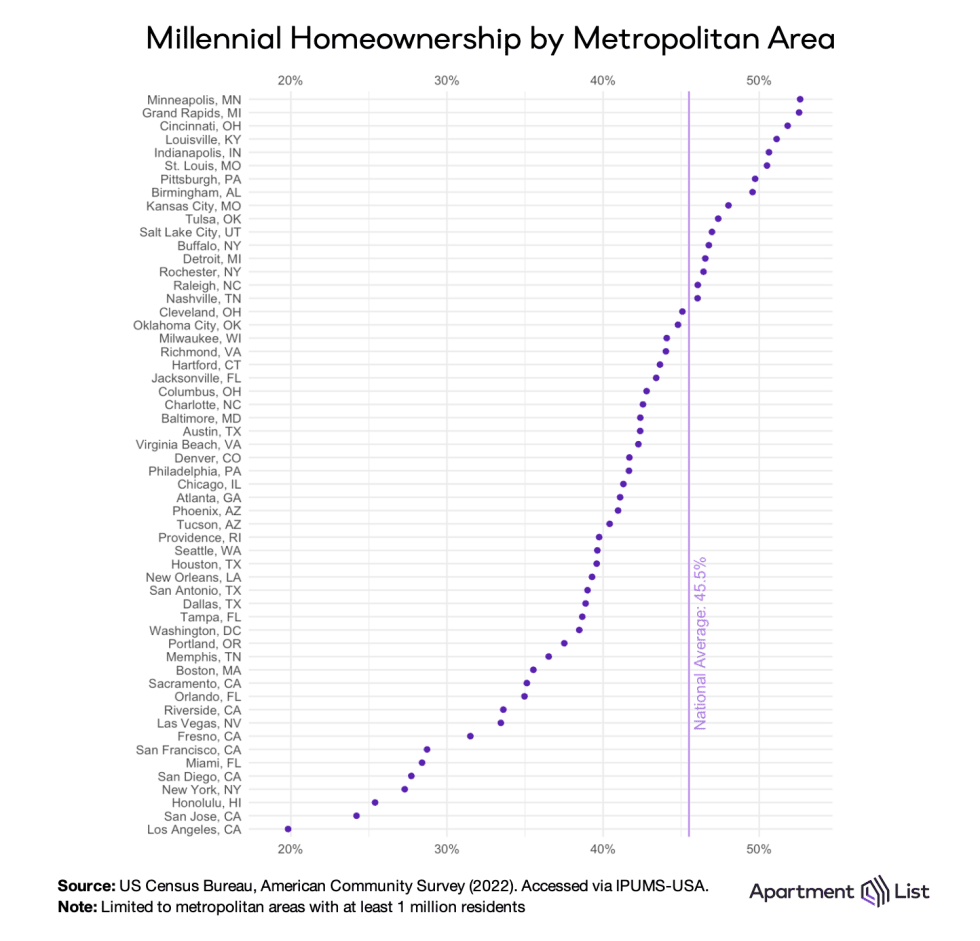

Millennials are finding the most success in smaller, Midwestern housing markets

One of the defining features of the housing market since 2020 has been a migratory shift away from dense, expensive cities and towards smaller, more-affordable ones. A number of pandemic-related trends emerged in 2020: high unemployment, expanded remote work opportunities, and demand for more physical space. And for many Millennials who had the means, this was a prime opportunity to buy a home. Today, the Millennial homeownership rate is highest (50 percent) in low-density non-metropolitan regions and gets smaller as metros get larger. It falls to 44 percent in markets of fewer than 1 million residents, 41 percent in markets of 1 to 5 million residents, and 33 percent in the nation’s largest metros.

In fact, only a handful of the nation’s large metros have a Millennial homeownership rate above the national average of 45%. The chart below displays 57 metros with a population of one million or greater. The Minneapolis metro sits atop the list (53 percent), followed by a number of markets concentrated largely in the Midwestern United States. Grand Rapids MI, Cincinnati OH, Louisville KY, Indianapolis IN, and St. Louis MO are the only other metropolitan areas where more than half of Millennials are homeowners.

It should come as no surprise that expensive coastal markets dominate the other end of the list. Among the ten metros with the lowest Millennial homeownership rate, six are in California: Los Angeles (20 percent), San Jose (24 percent), San Diego (28 percent), San Francisco (29 percent), Fresno (31 percent), and Riverside (34 percent). The remaining four are Honolulu, New York, Miami, and Las Vegas metros. Despite many of these markets offering high income opportunities, years of labor market growth without sufficient new home construction has left a dearth of affordable housing options.

The interactive map allows you to observe geographic patterns in Millennial homeownership at both the state and metro levels.

Other states that have historically been looked at as affordable housing markets, but whose home prices have skyrocketed since the pandemic – Florida, Arizona, Texas, etc. – also find themselves with below-average Millennial homeownership rates.

Gen Z homeownership is keeping pace with Millennials, for now

As Millennials grapple with the housing market into their 40s, the next generation is also getting old enough to start buying homes. As of 2023, 8 percent of Gen Z adults own a home, and so far their homeownership rate is trending in line with Millennials through their mid-20s. But Generation Z is coming of age during an affordability crisis unlike anything faced by earlier generations. In the past five years, home prices have surged 55 percent and elevated interest rates are further compounding the costs of owning a home. Rents have grown comparatively much slower than home prices, but are also up 20 percent. As a result, we see young adults not just renting longer but even waiting longer to move out on their own. At age 25, nearly 30 percent of Generation Z is still living with their parents, higher than any previous generation. If today’s affordability challenges persist, it’s very likely that Gen Z homeownership falls behind Millennials in the coming years.

What does this mean for the future?

We’re already seeing the housing market adapt to these homeownership trends. Anticipating that Millennials and Gen Zers will still want to live in single-family homes even if they can’t afford to buy them, the “built-for-rent” sector is booming. Nearly one-in-ten new single-family homes in 2023 were built to be rented instead of owned. Similarly, the past year has seen a flood of new multifamily units hit the market, which has helped moderate the cost of renting relative to owning.

One source of optimism for Generation Z and prospective first-time homebuyers is that the housing market is finally drawing widespread attention from policymakers, at every level of government. Housing has become a focal point of the upcoming presidential election, while many state and city governments have passed laws (often controversially) aimed at tackling the housing shortage directly. For example, in recent years Minneapolis became the first major city to eliminate single-family zoning, California began overriding local zoning laws in cities that are failing to build enough housing, and New York City placed severe restrictions on short-term rentals in the hopes of boosting supply for long-term residents. If successful, these experimental policies could build political momentum and pave the way for more-substantial reforms aimed at improving affordability and homeownership.

- Generations are assigned by birth year. Silent: 1928-1945. Baby Boomer: 1946-1964. Generation X: 1965-1980. Millennial: 1981-1996. Generation Z: 1997 or later.↩

Share this Article