More young adults now live with their parents than at any point since 1940

Introduction

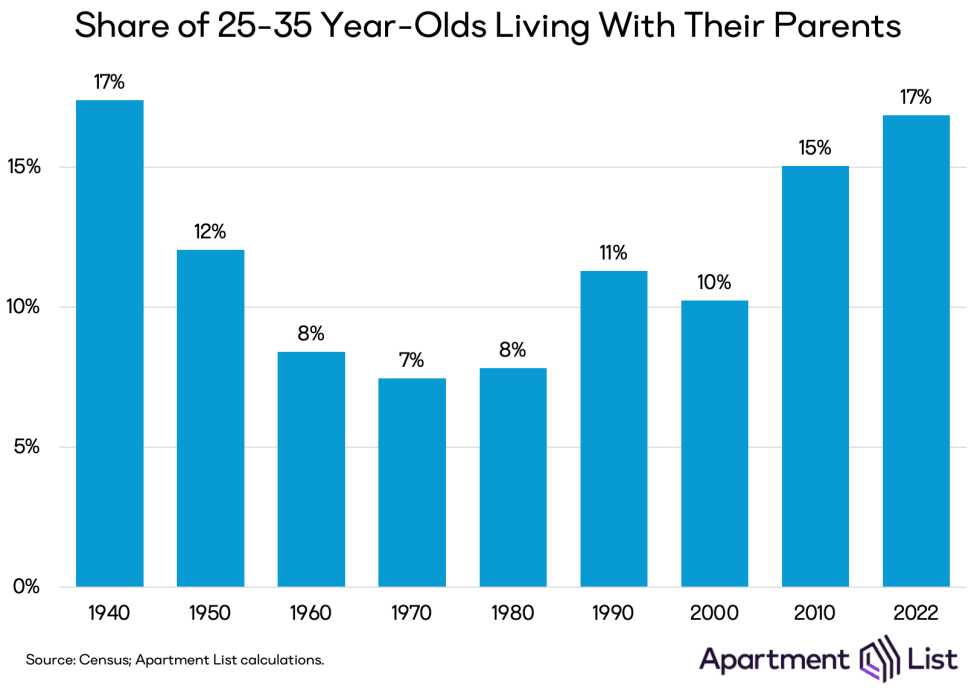

Moving out of one’s parents' house is often thought of as a key milestone on the path to adulthood. But in the face of waning housing affordability, a growing number of Americans are continuing to live with their parents into adulthood. In 1970, just 7 percent of 25 to 35 year-olds lived in their parents’ homes, but as of 2022, that share has more than doubled to 17 percent.

Those young adults who live at home today are also more likely to be there out of necessity rather than choice – fewer than one-in-five are earning incomes that would allow them to comfortably afford local rent prices, a far lower share than in the past. The prevalence of young adults living with parents is increasing in all parts of the country, and for both those with and without college degrees. In this report, we explore the long-term evolution of this trend.

The share of 25-35 year-olds living with parents is at its highest since the 1940s

When viewed over a long horizon, the share of young adults who live with their parents1 exhibits a U-shaped trend. In 1940, with the Great Depression still close in the rearview mirror, 17 percent of 25 to 35 year-olds lived at home. But in the ensuing decades, the postwar economic boom and rapid buildup of America’s suburbs enabled more young people to strike out on their own. From 1940 to 1960, the share of young adults living at home fell by more than half to 8 percent, and remained fairly stable at that level through 1980.

In the time since, however, the trend has reversed itself. Living with parents became slightly more common from 1980 to 2000, and from 2000 to today that growth has picked up even more steam. As of 2022 (the most recent Census data currently available) 17 percent of America’s young adults live with their parents, a rate that is more than double what it was during the low period from 1960 through 1980. The likelihood of 25 to 35 year-olds living with their parents has returned to a level not seen since 1940.

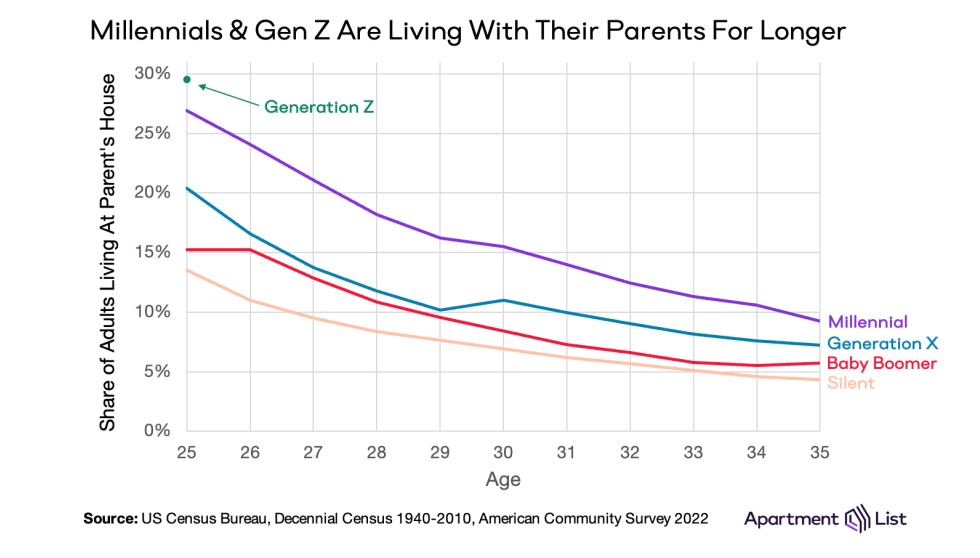

Another way of thinking about this trend is to make the comparison across generational cohorts. The chart below shows the percentage of adults who live with their parents at each age from 25 to 35, broken out by generation. As expected, we see living with parents become less common with age (i.e., it is more likely at age 25 than at age 35). More importantly, we also see the curves gradually shift up for each consecutive generation, as living with parents has become increasingly common over the course the past half-century.

The Silent Generation – the earliest cohort shown here – were born between 1928 and 1945, meaning that the oldest members of that generation turned 25 in 1953, while its youngest members turned 35 in 1980. In other words, the young adulthood of this generation largely coincided with the decades when the likelihood of living with parents was at its lowest.2 14 percent of the silent generation lived with their parents at age 25, and just 4 percent lived with parents at age 35.

From there, each generation has become more likely to live at home longer compared to the generation that preceded it. Baby Boomers and Generation X saw modest increases, while the bigger jump over the past two decades is represented by Millennials. 27 percent of Millennials lived with their parents at age 25, and 9 percent continued to do so at age 35. The oldest members of Gen Z are just beginning to enter the age range we analyze here, but early indications suggest that they are on track to continue the trend. In 2022, 30 percent of 25 year-old Gen Z members lived at home, an even higher share than that of Millennials at the same age.

The increased prevalence of living at home reflects waning housing affordability

While the charts above present a clear and persistent trend, they do not necessarily explain its causes. However, when we take a closer look at the economic characteristics of those living with parents, a clearer picture begins to emerge. For one, the incomes earned by this group have gradually declined in recent decades. In 2022, the median annual income of employed 25 to 35 year-olds who lived with their parents was $32,000. After adjusting for inflation, this was down by 10 percent compared to 2000.

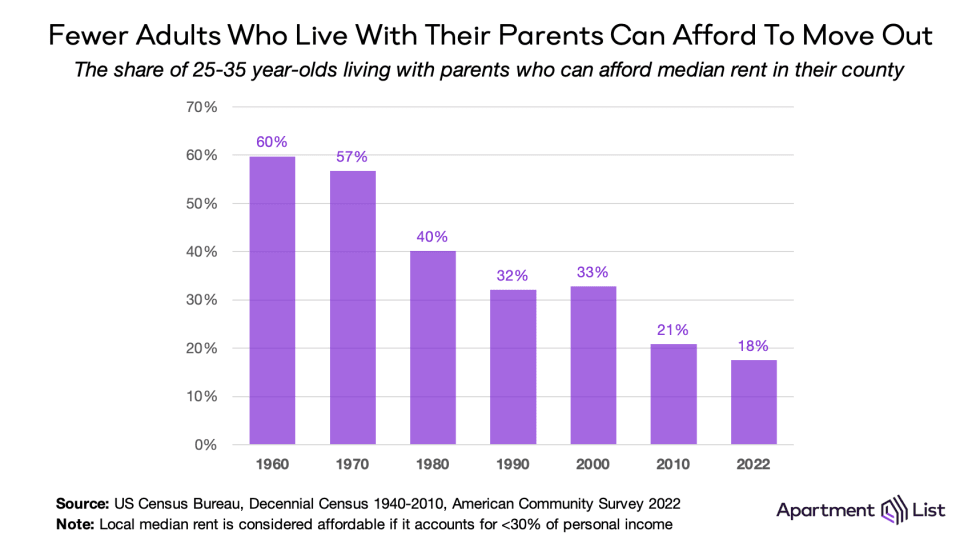

More importantly, this dropoff in income has been compounded by an even more dramatic increase in housing costs. Among young adults who live at home, the share who could comfortably afford to live independently has fallen dramatically. For the purpose of this analysis, we assume that an individual was in a financial position to move out of their parents’ home if they could have paid the median rent for studio and 1-bedroom apartments in the county where they lived without spending more than 30 percent of their individual income on rent.34

By our estimates, many of the young adults who lived with their parents in the past appear to have chosen that living situation as a matter of preference rather than financial necessity. We estimate that in 1960, 60 percent of the 25 to 35 year-olds who live with their parents could have afforded to rent their own nearby apartment. But in the ensuing decades, that share has consistently declined as rents have grown increasingly unaffordable. As of 2022, just 18 percent of young adults living at home were earning incomes that would have allowed them to comfortably strike out on their own.

Those with college degrees are less likely to live with parents, but the share is growing even for the highly educated

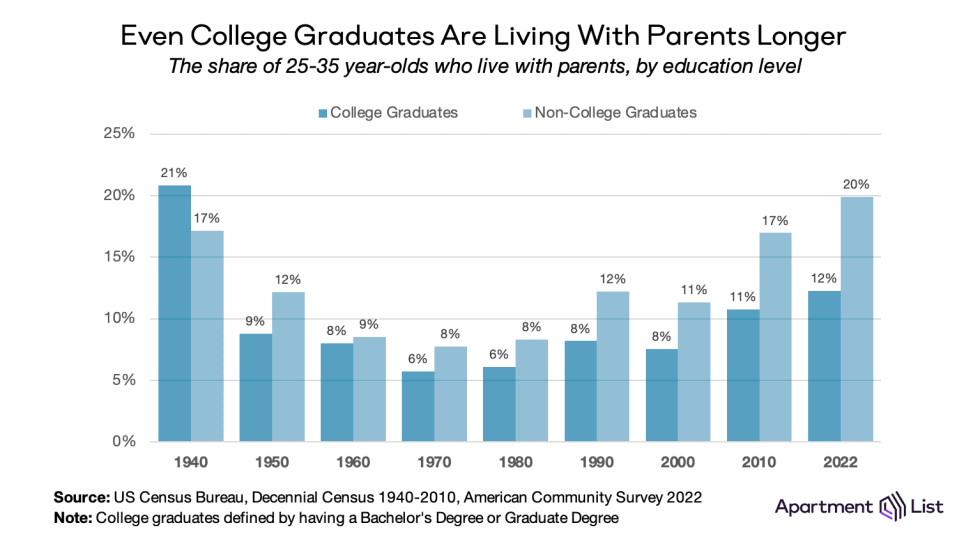

Over the long horizon that we analyze here, the U.S. has gradually shifted to a more knowledge-based economy, with a much greater share of Americans earning college degrees. Compared to prior generations, a college education has increasingly come to be seen as the safest path to economic security for today’s young people. This would seem to be validated by the fact that young-adults without college degrees are far more likely to live with their parents; one-in-five of them live at home, a rate that has more than doubled from just 8 percent in 1980. The non-college-educated make up 71 percent of all 25 to 35 year-olds who live with their parents.

But as higher education has grown more important, so too has its cost, to the point that student debt has risen to crisis levels. Even though college-educated young adults are less likely to live with their parents, the rate of living at home has increased substantially for this group as well. In 2022, 12 percent of 25 to 35 year-olds with a four-year degree or higher lived with their parents, up from 6 percent in 1980. Even though the college-educated account for less than one-third of young adults living at home, that share is higher than it’s ever been. And among degree-holding young adults who live with their parents, the share who could comfortably afford to rent their own place is lower than it’s ever been, without even taking into account student debt.

Living with parents is most common in expensive markets and those with stagnant local economies

This prevalence of living at home varies significantly across different parts of the country, but it’s rising virtually everywhere. Every single one of the nation’s 50 largest metros has seen the share of young adults who live with their parents increase between 2000 and 2022. In the Riverside, CA metro, that share has tripled over that period, from 10 percent in 2000 to 30 percent in 2022. This represents both the highest present-day rate among large metros, and the sharpest increase over the past two decades. The neighboring Los Angeles metro ranks second on both counts, highlighting the stark worsening of housing affordability in Southern California.

The Miami and New York City metros rank third and fourth in 2022, offering further evidence that this trend correlates with housing affordability. But this isn’t strictly the case – more affordable markets such as New Orleans, Detroit, and Chicago also rank in the top 10. These are markets where economic growth has been more stagnant, indicating that the story isn’t solely one of housing affordability, but also one of economic opportunity.

And at the other end of the spectrum, some of the markets where living at home is least common have seen rapid increases in housing costs. The Nashville, Austin, Denver, and Seattle metros all rank in the top five for the lowest shares of young adults living with their parents. These markets have all experienced a notable waning of housing affordability to varying degrees, but they have also all experienced booming economic growth. Large numbers of young adults have moved to these markets for high-paying job opportunities, offsetting rising housing costs.

Conclusion

As housing affordability worsens, more young people are remaining in their parents’ homes for longer. Some of these young adults are likely living at home by choice in order to build up a financial foundation more quickly. A majority, however, appear to be responding to financial necessity, finding themselves in positions where their incomes simply can’t match local rent prices. Living at home is more prevalent among those without degrees, but the number of college-educated young adults who live with their parents is also higher than it’s ever been, as growing student debt exacerbates the pressure of high housing costs. This trend speaks to the way in which today’s economic realities are forcing many of America’s younger generations to delay major milestones on the path to adulthood.

- In this report, we flag an individual as living with their parents only when the parent is identified as the head of household. This excludes situations in which a parent is living in their child’s household.↩

- The earlier peaks shown in the decade view above correspond to the Greatest Generation (born from 1901 to 1927), not shown here.↩

- This 30 percent threshold is a common benchmark for housing affordability; those who spend more than 30 percent of household income on rent are considered to be “cost-burdened.”↩

- Note that this may be a conservative definition, as some of those individuals who could not afford to live on their own may still have been able to comfortably afford to live with roommates. While the exact shares in this analysis are sensitive to the affordability definition used, the trend over time is robust across various definitions.↩

Share this Article