Rich and Renting: Understanding the Surge of High-Earning Renters

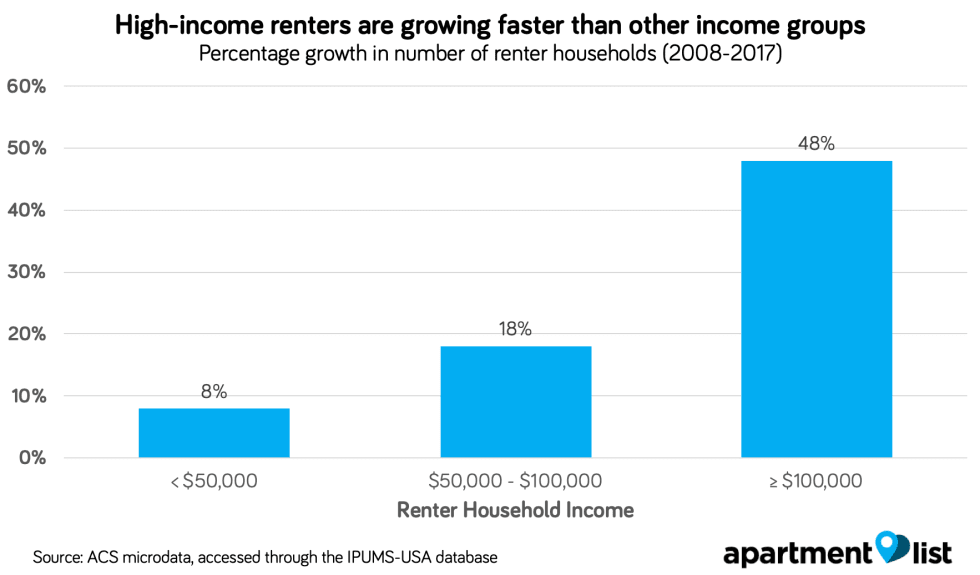

- High-income renter households -- those earning at least $100,000 per year -- represent the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. housing market. This group grew 48 percent from 2008-2017, when nearly 2 million high-income households became renters.

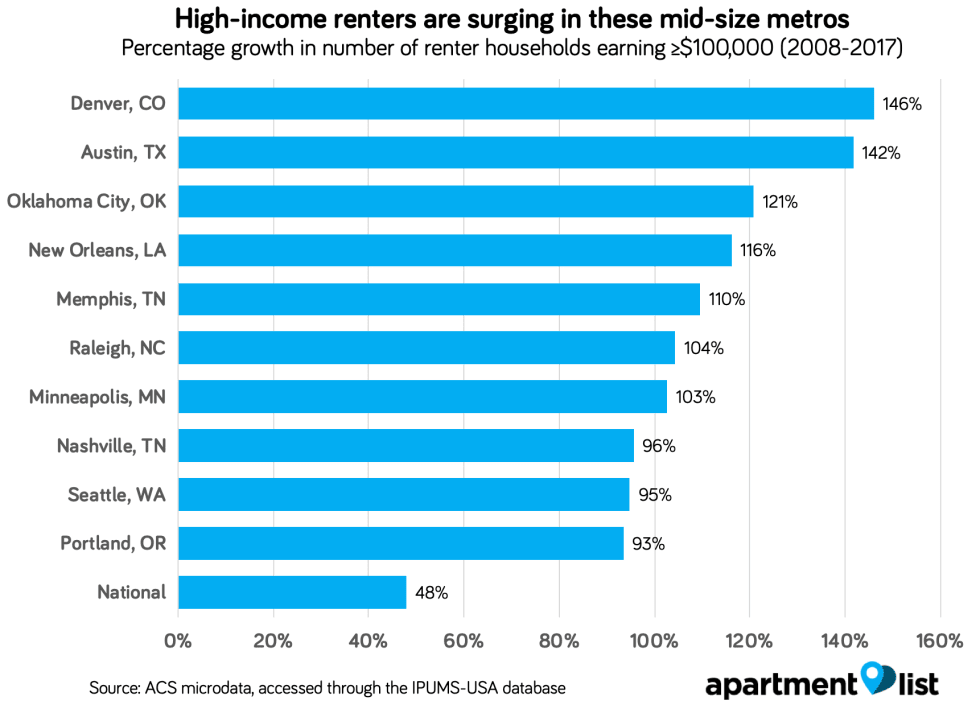

- The rise of high-income renters has been most dramatic in mid-size, growing metropolitan areas, particularly Denver (146 percent growth), Austin (142 percent), and Oklahoma City (121 percent). Growth is slower in America’s largest and most expensive markets, including New York (26 percent), Los Angeles (33 percent), and San Francisco (65 percent).

- While high-income renters are surging, renting as a whole is also on the rise. Over the past decade, the nation’s renter population has grown by 15 percent, with increases at all levels of income. High-earners have grown 48 percent, renters earning $50-100k have grown 18 percent, and renters earning <$50k have grown 8 percent.

- We document four factors that drive high-earners into the rental market: the recent boom in multi-family construction, the growing abundance of single-family home rentals following the Great Recession, increasing barriers to homeownership, and rising demand for both centrality and flexibility.

The Rise of High-Income Renters

Homeowners are richer than renters, but a recent wave of high-earning households are entering the rental market and closing this gap. Over the past ten years, the U.S. has seen a dramatic increase in the number of high-income renter households,1 from 3.8 million in 2008 to 5.7 million in 2017. Renter households earning six-figure salaries have become more common in nearly every segment of the country, from major metropolitan cities to the suburban and rural areas in between. During a time when the total population grew by 6 percent and incomes grew by 7 percent, the number of high-income renter households grew by a whopping 48 percent.

Denver and Austin lead the nation in high-income renter growth. These metros housed nearly 2.5 times more six-figure renter households in 2017 than they did in 2008. Other high-growth metros include mid-size, growing cities that attract transplants with their mix of strong economies and relatively low rents, including Oklahoma City (121 percent growth), Memphis (110 percent), and Nashville (96 percent). The top 10 are listed below, alongside the national average.

Notably absent from this list are the nation’s largest and/or most expensive metros, like the San Francisco Bay Area, New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. In part, these cities boast lower growth rates because they already had a large baseline population of rich renters in 2008. Supply constraints in these cities, however, have also played a role in restricting housing options for prospective high-earning renters. As a result, smaller metros that offer strong job opportunities at a lower cost of living saw the greatest change.

The trajectory and timing of high-income renter growth also vary across metros. Washington, D.C., and technology hubs like Seattle, San Jose, and Austin have experienced virtually uninterrupted growth over the past decade. Las Vegas, on the other hand, was significantly damaged by the Great Recession and did fully not recover its high-income renter population for nearly 8 years, despite its overall renter population growing steadily during this time. Atlanta, Columbus, Milwaukee, and San Diego followed similar paths, albeit on shorter timelines.

High-earning households are not the only expanding renter group. The total number of renters in the U.S. has grown 15 percent over the past decade, with new renter households being formed at all income levels. High-earners, however, entered the rental pool significantly faster than others, resulting in a sizable shift in the population.

Why are High-Earners Choosing to Rent, and Why Now?

What is luring these well-off households into the rental market? We document four factors: the recent boom in multi-family construction, the growing abundance of single-family home rentals following the Great Recession, increasing barriers to homeownership, and rising demand for both centrality and flexibility. The result is that a combination of new, appealing rentals (growing supply) and an increase in the relative ease and attractiveness of renting (growing demand) are reinforcing one another.

Growing Supply

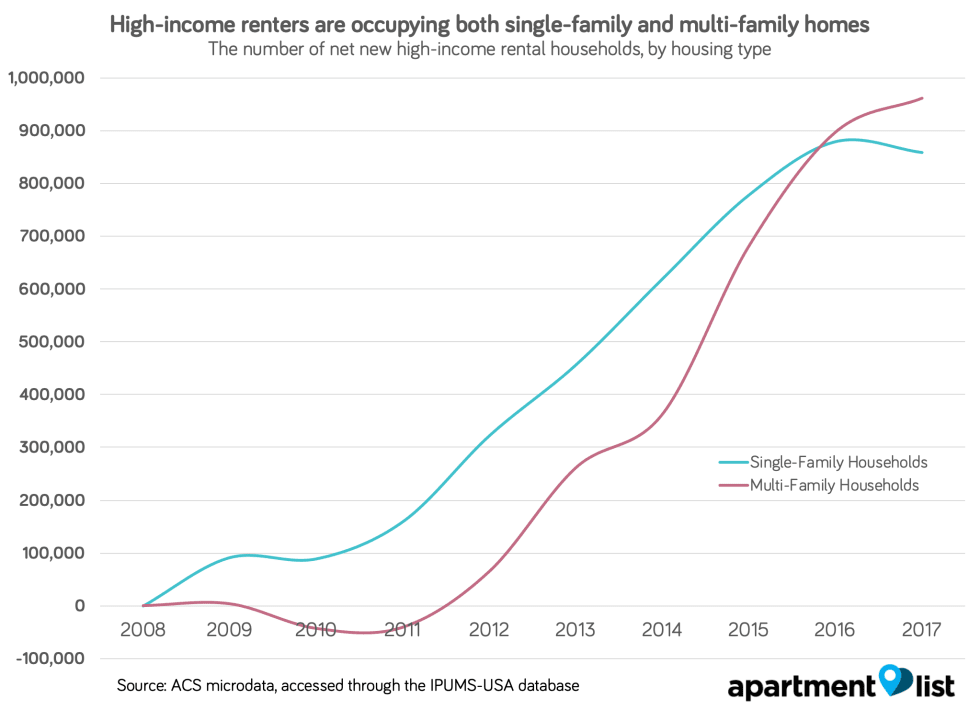

Since the Great Recession, new supply in the marketplace has provided high-earners with abundant rental options. An initial wave of single-family vacancies catered to those who value the comfort of suburbia, whereas a subsequent wave of multi-family construction catered to those who value centrality and urban living.

- Single-family supply: Before the Great Recession, the United States was in the midst of a decades-long residential construction boom stretching back to the post-WWII era. In 2008, however, as new sales declined and foreclosures spiked, an abundance of single-family homes became vacant. Taking advantage of the resulting low prices, investors scooped up many of these homes and converted them into rental properties. As a result, nearly 4 million single-family rentals hit the market, making this the fastest growing supply segment in the housing market. This new inventory enabled more high-income households to enjoy the extra space of single-family homes without needing to buy. Those desiring a suburban lifestyle increasingly had ample rental options.

- Multi-family supply: During the first three years of the recession, as single-family rentals were surging across American suburbs, funding for new housing construction had mostly evaporated. But in 2011, the multi-family sector roared back to life and brought new renter-friendly housing to dense urban cores. As we previously analyzed, multi-family construction quadrupled between 2010-2017 and has returned to pre-recession spending levels. Most of this supply was geared towards the higher end of the market, providing new amenities for high-income renters at a time when single-family home construction lagged.

In the chart above, we track new high-income renter households by housing type. From 2008-2011, high-income renters left multi-family homes in favor of the vacant single-family homes left behind from the Great Recession. Then, following the resurrection of multi-family construction in 2011, high-income households moved into these homes at such a fast rate that they overtook single-family in just five years. By 2017, there were a total of 1.8 million new high-income renter households - 960,000 occupying multi-family and 860,000 occupying single-family.

Growing Demand

While new rental supply was coming online, rental demand among high-income households was also on the rise. This new demand stems from two sources: barriers that prevent high-earners from purchasing homes, and migration patterns that concentrate high-earners in regions where renting is more prevalent.

- Greater barriers to homeownership: Since the Great Recession, a number of economic factors have made it difficult for many Americans to afford a home. Mortgage credit requirements have become more stringent, incomes have risen, but at a slower rate than home prices, and particularly for younger Americans, student-loan debt is making it difficult to save for a down payment. These challenges do not only impact America’s poor; the effects are felt even by high-earners who are traditionally more capable of owning a home. Apartment List recently surveyed millennials about this very topic, and even among high-income respondents2 who say they want to own a home in the future, only 5 percent believe they will be able to do so within the next year. Additionally, 63 percent said that affording a down payment is a major obstacle to their homeownership goals, and 69 percent, despite having high incomes, have less than $10,000 saved for a down payment. Until the economic landscape changes, renting may remain the most financially feasible option for many high-earners.

- A shift towards urban cores: High-income Americans are increasingly relocating to dense urban centers where renting and multi-family housing are more common. As observed by the University of Virginia’s Demographics Research Group, for the past several decades there has been an influx of younger, well-educated, and high-income individuals into city centers for the abundance of job opportunities and attractive amenities that exist there. Meanwhile, new technologies and the rise of the sharing economy have made it easier to move to city centers without sacrificing quality of life.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, households earning six figures have rapidly entered the rental market. As rental supply and demand both boomed, the homeownership rate fell steadily from 2008-2016. High-earning renters have multiplied especially quickly in mid-size, supply-abundant cities with strong economies. What does this mean for the future of the housing market?

- In the short-term, we expect the influx of high-earning households into multi-family rentals to continue, as multi-family construction remains strong and workers value the job opportunities and amenities of living in urban areas. With higher incomes, these households will demand new amenities from their homes and neighborhoods. High-income renter growth in the single-family segment began to level off last year, but it will take a major shift in housing affordability to completely reverse this trend.

- In the medium-term, we expect the growth of high-income renters to create both policy challenges and opportunities. On one hand, this trend will likely lead to greater inequality within the rental market. As cities debate solutions to disappearing affordability and gentrification, high earners are increasingly competing with everyone else for finite city space. On the other hand, these high-earning households may bring new momentum for policies that affect all renters. This may even solicit policy response at the federal level, which is currently a quiet topic which we expect to ramp up in the near future.

- In the long-term, this decade’s trend may be indicative of changing norms around how we pay for our housing. If today’s high-earning families increasingly value the centrality of living in cities or the flexibility of renting instead of owning, the traditional paradigm of homeownership as a paramount metric for financial success may begin to evolve.

Share this Article