Why the voter turnout gap between renters and homeowners may finally be narrowing

Introduction

With the 2022 midterm elections in less than two weeks, economic issues are taking center stage. Throughout this year, inflation has been running at its hottest pace in four decades, and there are growing fears that the Fed’s efforts to push back could induce a recession in the year ahead. Skyrocketing housing costs have been a key component of inflation, and one that could constitute a wedge issue between renters and homeowners. Most homeowners are locked into fixed monthly mortgage payments, and for those that already owned at the start of the pandemic, quickly rising home values have been primarily experienced as a boon to their net worths. In contrast, renters are bearing the full brunt of rising rent prices (nationwide, the median rent is up 23.4 percent since March 2020), and many of those hoping to purchase homes have been priced out of the for-sale market.

We’ve argued in the past that increased political engagement among a coalition of renters could have the potential to swing elections, and the upcoming midterms could prove to be a turning point where such a movement gains momentum. Renters have historically voted at far lower rates than homeowners, but that gap has been narrowing in recent years. Mobilizing renters could be a winning strategy for Democrats, the party that renters tend to favor by a wide margin. But given their present state of economic frustration and disenchantment, this large voting bloc could present an opportunity for either party. In this report, we explore the potential of a renter voting bloc to disrupt national elections, incorporating data on renter voting trends in prior elections, as well as a brand new survey of their current political concerns.

Historically, renters vote at significantly lower rates than homeowners, but the gap is shrinking

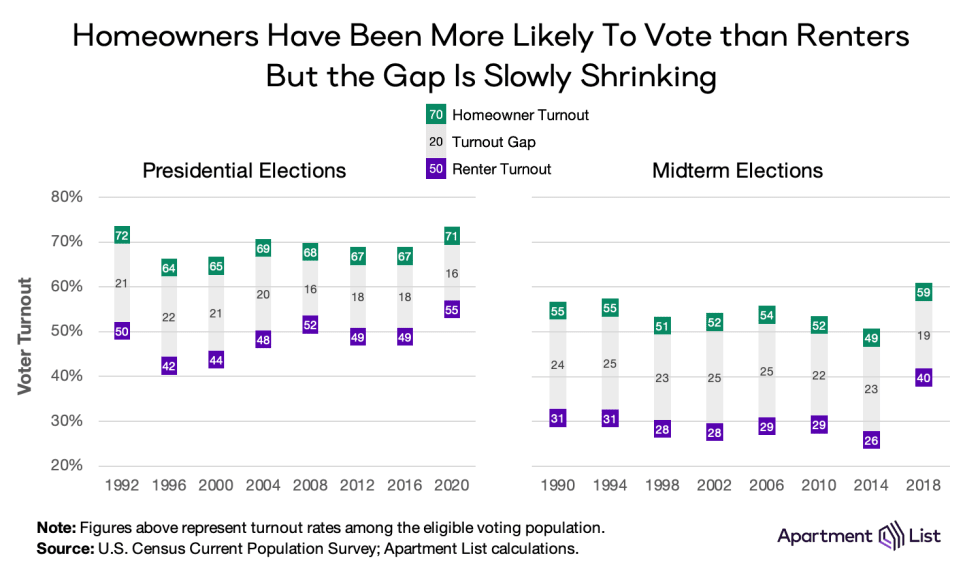

As we’ve noted in the past, the renter population is underrepresented at every step of the voting funnel. Compared to homeowners, renters are less likely to be of voting age, more likely to be non-citizens, less likely to be registered to vote even if they are eligible, and less likely to actually vote even if they are registered. There are various reasons for this disparity in political engagement, but a major one is simply property ownership. Homeowners have a large financial motivation to vote when they perceive that the policies at stake could impact local property values. Renters, on the other hand, face additional obstacles to voting. For example, renters are more likely to be struggling financially, such that taking the time to vote may exact a greater cost. Renters also move more frequently than homeowners, which could make it harder to maintain an active voter registration. And renters are far more likely to be members of minority groups who have been plagued by a long history of voter suppression. As a result, there is a wide gap in voter turnout that has persisted for decades. The chart below plots the turnout rates among eligible voters for renters and homeowners for every national election going back to 1990, based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey.1

The turnout gap has shown signs of narrowing in recent national elections. In the 1992 presidential election, 71.6 percent of eligible homeowners voted, compared to 50.2 percent of eligible renters, a gap of 21.4 percentage points. The following three presidential elections all also had gaps of more than 20 percentage points. But the gap narrowed significantly to 16.2 percentage points in 2008, when the candidacy of Barack Obama sparked increased turnout among minority voters, a disproportionate share of whom are renters. The gap increased again slightly in the 2012 and 2016 elections, but was still smaller than it had been in the pre-2008 elections. Most recently, the 2020 presidential election saw the highest turnout among renters of any election we looked at (55 percent) and the second smallest turnout gap (16.4 percentage points).

In midterm elections, voter turnout is significantly lower for both groups, and the turnout gap between renters and homeowners is wider. But here too, we see signs that this gap has been narrowing. In the five midterm elections from 1990 to 2006, the gap in voter turnout between renters and homeowners ranged from 23 percentage points to 24.9 percentage points. Then the 2010 and 2014 midterms saw slightly smaller gaps (22.2 percentage points and 22.8 percentage points, respectively). And most recently, in the 2018 midterms, the turnout gap fell again to 19.1 percentage points, the smallest gap of any midterm election we have data for. This narrowing gap was driven by renters in 2018 voting at a far higher rate than they had in any prior midterm (39.8 percent turnout). As housing costs soar and homeownership gets further out of reach for the nation’s renters, it appears that they may be expressing their growing frustration through increased political engagement.

When they do vote, renters favor Democrats heavily

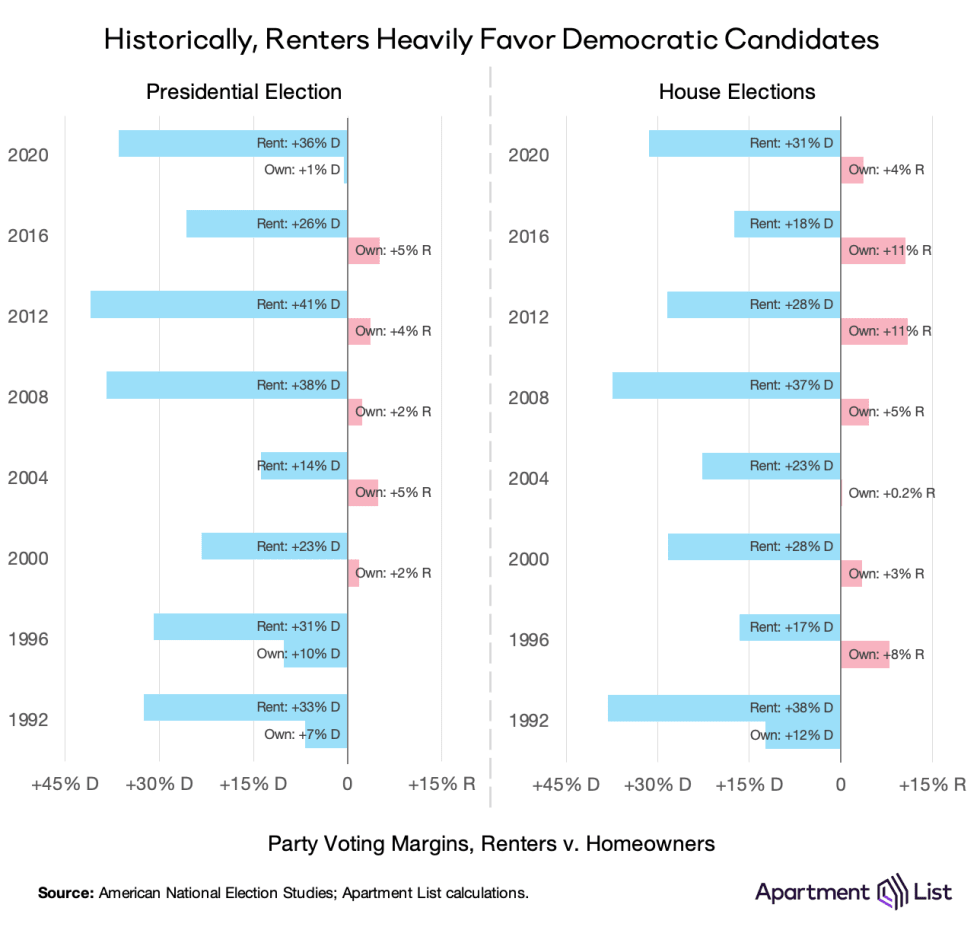

Renters may be far less likely than homeowners to show up at the polls, but when they do, they show a strong preference for Democratic candidates. In the 2020 presidential elections, renters favored President Biden over former President Trump by a staggering margin of 36.5 percentage points; homeowners, meanwhile, favored Biden by a razor thin margin of just 0.6 percentage points. And similar to the turnout gap, the partisan swing of renters is also a longstanding trend. Renters have not swung for a Republican presidential candidate since President Nixon in the 1972 election, and in every presidential election from 1992 onward, the Democratic candidate has won the renter vote by a double digit margin. Conversely, before tilting slightly for President Biden, homeowners hadn’t favored a Democratic presidential candidate since Bill Clinton in 1996.

This trend is not limited to presidential elections. In races for the House of Representatives, renters favored Democratic candidates by a margin of 31.4 percentage points in 2020, while homeowners favored Republican candidates by a margin of 3.7 percentage points. Similar to presidential races, renters have favored Democratic House candidates by double digit margins in every presidential election year going back to 1992.2

Given their extreme skew toward Democrats, increased turnout among renters has the potential to significantly alter the outcomes of election outcomes. We’ve shown previously that if voter turnout among renters had matched that of homeowners in the 2016 elections, Hilary Clinton would have beat former President Trump handily, and Democrats would have likely won additional seats in both the House and Senate. That said, over the past two years – during which Democrats have controlled the White House and both chambers of Congress – housing affordability has been eroding at a historically fast pace, with the national median rent up by 25.9 percent since President Biden took office. This could create an opening for Republicans to speak to renters who may feel disenchanted by the idea that Democrats are serving their needs.

Renters are far more likely to view housing as a key issue in the midterms

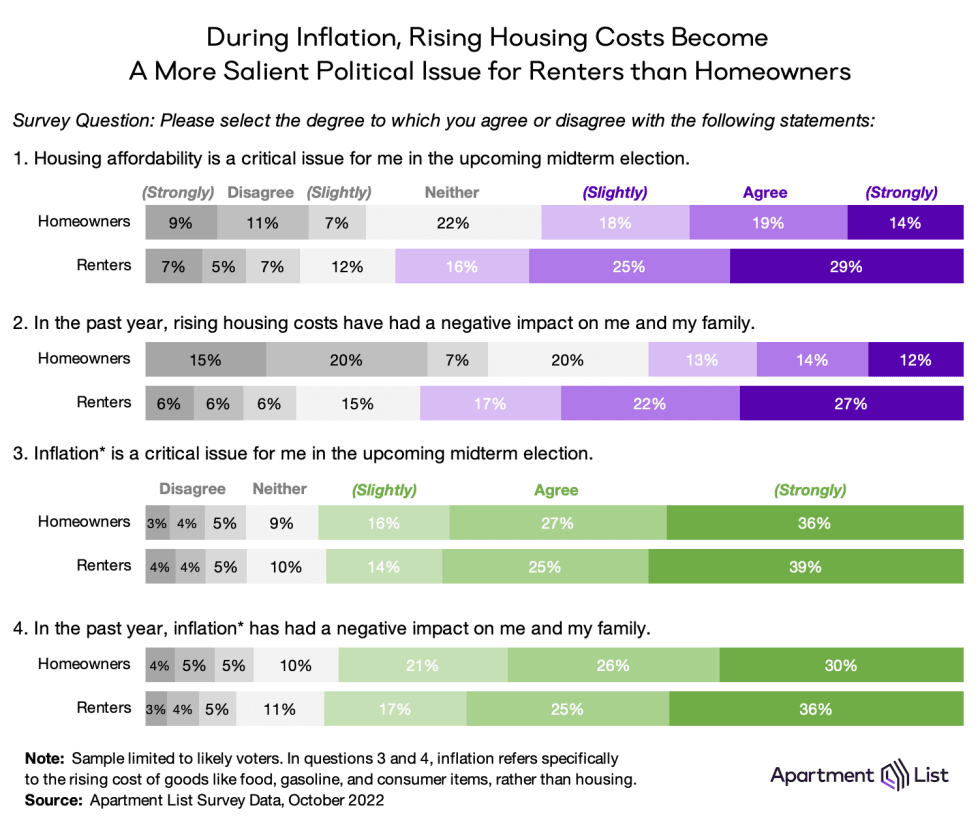

The economy has been extremely volatile over the past two years, and the most-recent stretch of inflation may shape how renters will respond at the ballot box in November. Renters are subject to the greatest impacts of rising housing costs, in addition to the broad general inflation that is making everyday goods more expensive, for everyone. To better understand how the economy is shaping their vote, our team surveyed over 8,200 registered voters in the weeks leading up to the 2022 midterms. This survey is an early signal that once again homeowners will turn out in greater volume, as 80 percent of homeowners said they are “very likely” to vote, compared to 61 percent of renters. Other survey questions suggest a continuation of the political trends that we’ve seen over the past several decades, including renters being more ideologically liberal.

With respect to today’s economy, our survey finds that inflation is a mobilizing topic for renters and homeowners alike, but the rise in housing costs specifically is much more impactful and influential to the renter vote. Surveytakers were asked to agree or disagree with statements about the importance of housing affordability in this election, as well as the detrimental effects of rising housing costs on them and their families. Similar questions were posed about the non-housing components of inflation, like the rising cost of food, gasoline, and other consumer goods.

Broad economic inflation has negatively impacted the majority of voters: 78 percent of renters and 77 percent of homeowners according to the green bars in the chart above. Unsurprisingly, roughly the same share believe inflation is a central issue to be addressed by the candidates in this election. But the largest single component of economic inflation hinges on rent growth, which ballooned nearly 18 percent in 2021. And the effects of this specific type of inflation are not nearly as universal.

In the purple bars above, 65 percent of surveyed renters said that rising housing costs have had a negative impact on their families, and to no surprise, roughly the same share say this is a critical issue affecting their vote. In contrast, only 39 percent of homeowners agree similarly about housing inflation. It may be unexpected that so many homeowners feel that this way, considering most have seen their net worths spike with rising property values. The homeowners who have been negatively impacted likely represent some combination of (1) recent buyers who have had to contend with difficult market conditions, (2) homeowners with adjustable-rate mortgages being impacted by higher interest rates, (3) rising property taxes, or (4) negative impacts on mobility among owners who feel that the current market conditions are keeping them locked into their existing home. On the flip side, a greater share of homeowners (42 percent) disagreed with the idea that rising housing prices are hurting them, confirming that home price inflation is actually economically beneficial for many households whose housing payments are fixed or nonexistent.

Our survey also demonstrates how for those experiencing the effects of inflation, housing affordability can be a politically-mobilizing force. Among renters who agree that rising housing costs have had a negative impact on their lives, 58 percent told us they have become more politically active over the past two years, while only six percent say they are less politically active. Interestingly, this mobilization is even stronger among the relatively small share of homeowners who are feeling the negative effects of housing inflation: 63 percent say they are more active today, while only six percent are less active.

What role could renters play in the upcoming midterms and beyond?

Renters represent a unique voting bloc – they make up over one-third of the population, are far more racially diverse than homeowners, and are united by a distinct set of economic concerns. Homeownership has historically been the primary engine for wealth creation in our country, and the net worth of the median homeowner is more than 40 times that of the median renter ($255,000 vs $6,300). While most renters still aspire to eventually own homes, they increasingly feel that it is out of reach. But the concerns of renters may not be fully appreciated by the politicians who represent them; in fact, nearly all members of Congress own their homes.

As rising housing costs drive an even deeper wedge in the wealth gap between renters and homeowners, there may be an opportunity for candidates to mobilize renters around the housing affordability crisis and related economic concerns. In fact there is some evidence that such a shift may already be starting to occur. In recent years, housing has been elevated from a fringe concern to a central one in the national discourse. At the federal level, the Biden administration recently released an ambitious plan to tackle housing affordability, and at the local level, tenant unions around the country are feeling growing momentum. At the same time though, for renters who are struggling to make ends meet, national politics may take a back seat to the stress of managing their day-to-day concerns. Previous survey research that we’ve conducted has shown that individuals who are struggling with their housing costs are less likely to vote.

Assuming that the present moment is ripe for renters to be politically mobilized as a distinct voting bloc, there remains the question of which party will capitalize on the opportunity. The past voting record shows that renters strongly favor Democrats. In fact, our prior research has shown that economic views of renters tend to be even further left that those of Democratic voters overall, with a stronger preference for strengthening the social safety net. At the same time, when asked specifically which party is better equipped to handle the nation’s economy, renters continue to favor Democrats, but by a margin of just 10 percentage points, far lower than the 30-plus point margins by which they favor Democratic candidates at the polls. As Republicans look to further their appeal with working class voters, speaking to the concerns of renters could be one way to do so.

Renter voices are significantly underrepresented in our nation’s politics, and boosting the voter turnout of this large demographic could have dramatic implications in the outcomes of elections. The most recent few national elections offer evidence that such a shift has already been starting to take place. And with the housing affordability crisis having rapidly grown in magnitude since 2020, there’s good reason to believe that political mobilization of renters may continue to pick up steam in the upcoming 2022 midterms and beyond.

- Census reported voter turnout by housing tenure in elections going back to 1978, but for pre-1990 elections, this data was provided for heads of household only, such that the figures are not directly comparable. That said, this data suggests that the homeowner vs renter turnout gap may have been even larger in earlier decades. For instance, the turnout gap among voting eligible heads of households was 23.6 percentage points in the 1980 presidential election and 29.2 percentage points in the 1978 midterms, both notably larger gaps than we see in any of the elections from 1990 onward.↩

- The American National Election Studies surveys that we rely on for this analysis are only available in presidential election years from 2004 onward. While data are available for earlier midterm elections, we focus on presidential election years here for consistency. Data from midterm elections in 2002 and earlier confirm that renters tend to favor Democratic candidates by wide margins in the midterm elections as well, with the sole exception of 1998.↩

Share this Article