Rental Insecurity: The Threat of Evictions to America’s Renters

Apartment List is committed to improving the process of renting, and as part of that mission, we publish research on issues that impact both renters and landlords. In this report, we study the prevalence of evictions, an issue that has serious implications for renters, and often for landlords as well. Our data shows that the vast majority of evictions are the result of non-payment of rent. Apartment List does not endorse the views or opinions of any individuals mentioned in this article, including Matthew Desmond.1

- Analyzing data from Apartment List users, we find that nearly one in five renters were unable to pay their rent in full for at least one of the past three months. We estimate that 3.7 million American renters have experienced an eviction.

- Evictions disproportionately impact the most vulnerable members of our society. Renters without a college education are more than twice as likely to face eviction as those with a four-year degree.

- Additionally, we find that black households face the highest rates of eviction, even when controlling for education and income. Perhaps most troublingly, households with children are twice as likely to face an eviction threat, regardless of marital status.

- The impacts of eviction are severe and long-lasting. Evictions are a leading cause of homelessness, and research has tied eviction to poor health outcomes in both adults and children. These effects are persistent, and experiencing an eviction makes it difficult to get back on one’s feet.

- Performing a metro-level analysis, we find that evictions are most common in metros hit hard by the foreclosure crisis and in those experiencing high rates of poverty. Perhaps counterintuitively, expensive coastal metros have comparatively low rates of eviction, in part because strong job markets with high median wages offset expensive rents in those areas.

Introduction

Earlier this year, urban sociologist Matthew Desmond won the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction for his book, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. Last month, at a public policy forum on eviction in Madison, N.J., Mr. Desmond spoke about the issue of evictions with New Jersey Sen. Corey Booker, just months after the local newspaper, the Asbury Park Press, published a series on evictions, headlined, “Renter Hell.” And, from Philadelphia to Denver, policymakers are discussing solutions for renters who face evictions.

Clearly, America is increasingly confronting the eviction crisis that its renters face. But, with that said, it is difficult to address a problem that we can’t fully measure, and there is currently a serious lack of comprehensive nationwide data on evictions. Using court records, we can track evictions adjudicated in legal proceedings, but those records are not stored in a central database and fail to capture the many evictions that occur informally. For every household that goes through eviction, there are many others struggling to pay rent and living with the threat of eviction close at hand.

To help add to this discussion, Apartment List analyzed data from our users to explore eviction trends for the nation as a whole, as well as estimating eviction rates at the metro level. We found that many renters struggle to pay their rent, with nearly one in five survey respondents reporting that they were unable to pay their rent in full for at least one of the past three months.

Missed rent payments often lead to eviction, which uproots households, destabilizes families and communities and creates an instability from which it can be extremely difficult to recover. Evictions are a leading cause of homelessness, and research shows that frequent moves lead to poor educational performance and increased behavioral problems in children. Even when they do not face eviction, members of households that struggle to pay rent live with the fear of housing insecurity, which often means sacrificing other basic needs, such as food and transportation.

For years, rent growth has outpaced wage growth, and a severe lack of affordable housing affects many parts of the country. Although programs, such as Section 8, provide assistance for low-income renters, these programs are underfunded, and only a small share of those eligible for benefits actually receive them. Understanding the national crisis that America faces, with evictions, is a critical part of improving the conditions of families across the nation.

Data and Methodology

To contribute to the research on the complex issue of rental insecurity, Apartment List dug into data from our millions of users to examine trends at the national and metro levels. We collected detailed data on rental security through our annual renter survey, which has gathered over 41,000 responses.

Survey questions related to rental insecurity include:

- In the last three months, has there been a time when you were unable to pay all or part of the rent?

- Have you been threatened with eviction in the last year?

- What was the primary reason for threatened eviction?

- Was the move from your most recent prior residence the result of an eviction?

Our survey also captures information on location and various demographic traits, such as race, educational attainment and family status. For metro-level breakdowns, we analyze anonymized data on prior evictions from over eight million registered Apartment List users.2 We weight survey responses and user data by income, in order to align the income distributions for these datasets with the actual distribution for the U.S.3

3.7 million Americans have experienced eviction, with rental insecurity affecting nearly one in five

Our Apartment List estimates show that 3.3 percent of renters have experienced an eviction at some point in the past, and 2.4 percent were evicted from their most recent residence. With an estimated 118 million renters in the U.S. today, we estimate that 3.7 million Americans have been affected by eviction at some point. If we assume that some share respondents fail to report informal evictions, this estimate is most likely understated.

While experiencing eviction is a worst-case scenario with dire effects, a much larger share of renters still struggle with some form of rental insecurity. Our analysis shows that 18 percent of respondents had difficulty paying all or part of their rent within the past three months. The issue is particularly acute for low-income renters, 27.5 percent of whom were recently unable to pay their full rent.

When households are unable to reliably pay rent, they live in uncertainty, with the risk of eviction looming. Low-income renters, in this situation, often have to choose between paying rent and providing for their other needs, and avoiding eviction often means cutting back on other essentials, including food.

We find that 7 percent of respondents were threatened with eviction within the past year, which is more than double the share that was evicted from their previous residence. This is likely due in part to the fact that many renters choose to move voluntarily to avoid eviction. While doing so allows a renter to maintain a clean eviction record, moving under these stressful circumstances still poses many of the same problems as an actual eviction.

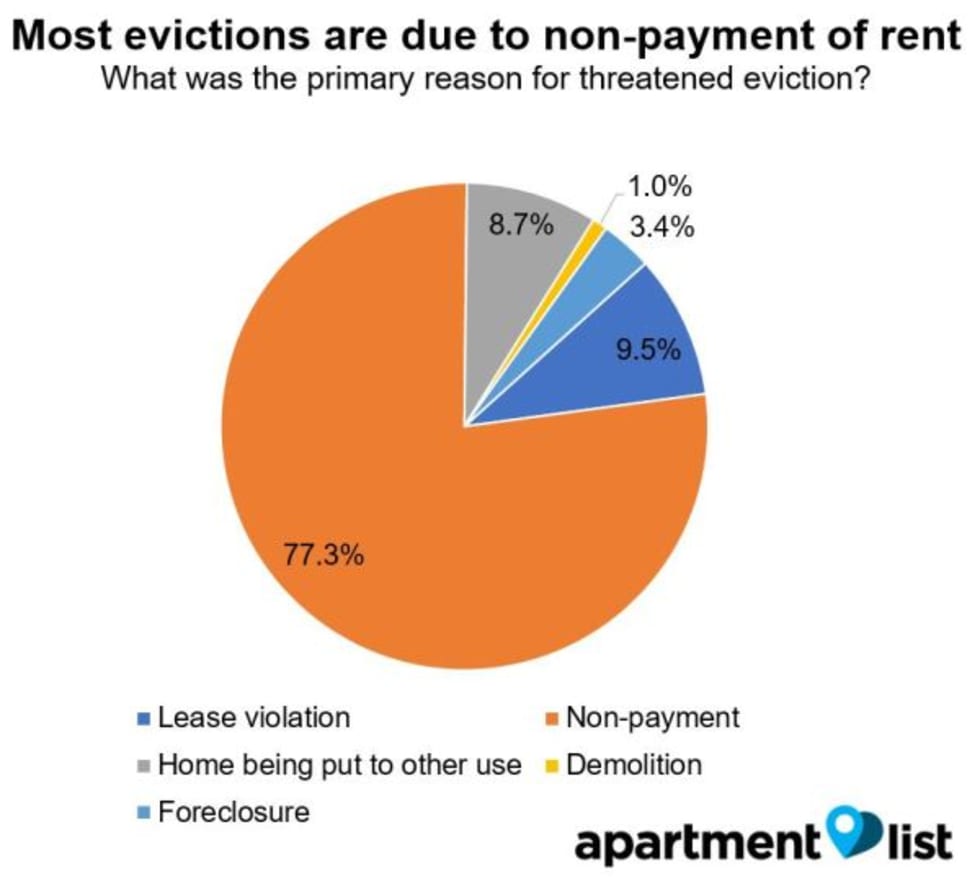

The vast majority of evictions are due to non-payment of rent4

Our analysis shows that 77.3 percent of eviction threats were due to non-payment of rent. An additional 9.5 percent were due to other lease violations, while the remaining 13.2 percent of eviction threats were due to factors outside the renter’s control, such as a home being put to another use, foreclosure or demolition.

Renters without a college education are twice as likely to have been evicted

Evictions disproportionately impact those on the lower rungs of the education ladder. We find that respondents with just a high school diploma are more than three times as likely to have faced an eviction threat in the past year than those with a Bachelor’s degree.

Of those who did not attend college, 4.1 percent cited an eviction as the reason for their last move, compared to just 1.9 percent of those with at least some college education. This trend points to a broader issue of the housing market leaving behind less educated Americans. A recent Apartment List study showed that the gap in homeownership rates between high school and college graduates widened from 1.6 percent in 1980 to 14.9 percent in 2015.

A similar trend holds when broken down by income. Of those earning less than $30,000 per year, 11 percent faced an eviction threat in the past year, and 3.4 percent were evicted from their previous residence. In contrast, for those earning more than $60,000 per year, these figures are 3.1 percent and 1.5 percent, respectively.

Black households more than twice as likely to face eviction compared to white households

When breaking down the data by race, we find that 11.9 percent of black households faced an eviction threat in the past year, compared to just 5.4 percent of white households. Asian households are least likely to face eviction, with just 2.5 percent of Asian respondents reporting a threatened eviction in the past year. This holds true even when controlling for education.

For those with a high school diploma or less, 15.2 of black respondents reported facing an eviction threat within the past year, compared to 10.5 percent of white households and just 5.6 percent of Asian households. This racial disparity holds for more educated respondents, as well; black households have the highest eviction rates at all levels of educational attainment. We obtained similar results when controlling for income; 15.6 percent of low-income black respondents faced an eviction threat, compared to 9 percent of low-income white respondents.

Perhaps, surprisingly, our data show that Hispanic households tend to have lower eviction rates than white households. If we assume that some share of Hispanic respondents are undocumented immigrants, this result may suggest that such households are more likely to move voluntarily to avoid an eviction record, for fear of deportation.

Households with children twice as likely to face an eviction threat, regardless of marital status

We also looked at breakdowns by family status, placing respondents into four groups, based on their marital status and the presence of children in the household. The data show that households with children are much more likely to have difficulty paying rent, regardless of marital status.

Single parent households are at the highest risk, with 30.1 percent reporting difficulty paying rent within the past three months. However, married couples with children do not fare much better, with 27.2 percent struggling to pay rent. For those without children, the rates are 14.7 percent for single respondents and 13.3 percent of married respondents. Our findings are consistent with previous research showing that, among tenants who appear in eviction court, those with children are significantly more likely to be evicted.

This result points to the fact the child care represents an essential but often overwhelming expense for many families, even those with both parents in the house. Analysis from Care.com shows that average daycare costs for toddlers range from $8,043 to $18,815 per year. Furthermore, one-third of families surveyed reported that childcare costs take up 20 percent or more of their household income.

Evictions have long-term impacts

The finding above is particularly troubling because it implies that a large number of young children are suffering from the negative impacts of unstable housing situations. Experiencing an eviction at a young age can have serious, long-lasting consequences on childhood development.

Research from Matthew Desmond, Princeton sociologist and author of Evicted, shows that mothers who experienced a recent eviction are more than twice as likely to report poor health in their children compared to those who did not experience eviction but share otherwise similar traits. The same study found these effects to be lasting, with evicted mothers still reporting significantly higher rates of material hardship and depression two years after eviction. The authors state that “because the evictions we observed in our sample occurred at a crucial developmental phase in children’s lives, we expect them to have a durable impact on children’s wellbeing.”

Lasting impacts of evictions are consistent with our data, which shows that those who were evicted from their previous residence are more than twice as likely to have missed a rent payment in the last three months, compared to those who were not previously evicted. The eviction process can be quite expensive, making it difficult for the evicted to get back on their feet, and having an eviction record can make it extremely difficult to find future housing.

Eviction rates highest in the South and Midwest

With data on millions of users across the nation, we are able to estimate eviction rates at the local level for metros across the country. We find that many of the metros with the highest eviction rates are located throughout the South and Midwest, while perhaps surprisingly, more expensive coastal metros tend to have lower eviction rates.

Highest eviction rates in metros with widespread poverty

Of the 50 largest metros in the nation, evictions are most prevalent in Memphis, with 6.1 percent of users reporting a prior eviction. Most of the metros with the highest eviction rates are located in the South and Midwest and include Atlanta, Indianapolis and Dallas. We find that the factors most strongly correlated with eviction rates include (1) the rate of foreclosures from 2007 to 2008, during the height of the foreclosure crisis, and (2) current poverty rates.

Memphis, for example, has the highest share of its population living in poverty at 19.4 percent, and it also has the highest eviction rate. In metros with high poverty rates, many households may qualify for assistance through programs such as Section 8, but, unfortunately, only a small share of those eligible for such benefits actually receive them, leaving the majority of low-income households struggling to pay rent.

Las Vegas had the second highest foreclosure rate from 2007 to 2008 at 9.2 percent and now has the sixth-highest eviction rate at 5.5 percent. This correlation suggests that many of the areas hit hardest by the foreclosure crisis have had a difficult time recovering. Despite lower housing costs, renters in these areas -- some of whom are likely former owners who had their homes foreclosed upon -- face a lack of opportunity that makes it difficult for them to pay their rent.

Some of the most expensive metros have the lowest eviction rates

Although displacement of long-time renters is a sensitive and high-profile topic in fast-gentrifying markets such as the Bay Area, these metros actually tend to have lower overall eviction rates. The list of metros with the lowest eviction rates contains locations well-known for their lack affordability, such as San Jose, San Francisco, Boston and New York. While this result may seem counterintuitive, it seems to be driven by the fact that the most expensive areas also tend to have the best job opportunities. We find that median income and rent growth over the past 10 years are both negatively correlated with evictions.

Despite high costs and fast rent growth in many of the metros above, the majority of renters in these markets have high incomes that offset the expense. Additionally, because of their thriving economies, housing markets in these metros are also more competitive, meaning that renters who are more likely to have difficulty paying rent will find it difficult to find an apartment in the first place.

This is not to say that evictions do not pose a problem for these cities. It’s important to note that our analysis is done at the metro level, meaning that we do not capture nuance in how eviction rates vary within metros. For example, the San Francisco metro contains a number of wealthy suburbs where evictions are likely rare. However, certain neighborhoods in the urban core surely experience much higher eviction rates.

The role of tenant protections

Local laws that protect tenant rights are another important factor affecting the prevalence of evictions in a given location. Rent control, which places a ceiling on the amount that landlords can increase rents, is a well-known form of renter protection, though these laws are actually fairly rare. Another example is what are known as “just cause” eviction ordinances, which limit the ability of landlords to arbitrarily evict tenants.

While differences in tenant protection laws certainly play a role in explaining the variations that we observe in metro-level eviction rates, the exact impact is difficult to measure. Such ordinances are enforced at the local level, meaning that specific protections vary even within a given metro, and there is no comprehensive measure to compare the relative strength of tenant protections by location. That said, the ranking of metros in our analysis does seem to generally coincide with what experts on the issue might expect. According to Philip Verma of the Center for Community Innovation at UC Berkeley, the California metros that we rank as having some of the lowest eviction rates are also well known for having some of the strongest tenant protection laws.

Conclusion

Nearly one in five renters have difficulty paying rent, putting them in a tenuous position where the threat of eviction is never far out of mind. Evictions disrupt families and communities, imposing further harm on what are often the most vulnerable members of our population.

The prevalence of this issue demonstrates the need to allocate additional resources to prevent evictions. This includes additional funding for Section 8 rental assistance programs, which are effective but underfunded, serving only a small share of those who are eligible for benefits. Given that many evictions are the result of temporary hardship, increasing the availability of short-term loans to help low-income renters avoid missed payments would also likely be effective.

The costs of expanding such benefits would be at least partially offset in the immediate term by reducing related costs associated with homelessness and health care. In the long term, reducing rental insecurity can help create more safe and stable communities which provide their residents with a greater chance at success.

Download Data Here5

- Added November 17, 2017.↩

- Survey and user data is self-reported and the word “eviction” is not explicitly defined; the extent to which we capture informal evictions is, therefore, subject to respondents’ interpretations of the question.↩

- Users and survey respondents are grouped into the following income buckets: households earning less than $30,000 annually are defined as low-income, those earning $30,000 to $60,000 are defined as middle-income, and those earning over $60,000 are defined high-income. For each sample, the share falling into each income bucket is compared to the true distribution obtained from Census ACS 2016 1-year estimates, and samples are reweighted accordingly. Survey data is weighted at the national level, and user data is weighted at the metro level.↩

- Added November 17, 2017.↩

- Data updated 1/22/2020↩

Share this Article