Not Everyone Loves the Remote Work Revolution

Introduction

The remote work revolution has been a transformational force for the housing market. In 2020, the rapid adoption of remote work (coupled with a spike in unemployment) gave millions of workers greater flexibility to move somewhere new. Two years later, employment is back near pre-pandemic levels but office attendance is not, and housing markets have experienced rapid changes in availability and affordability as workers settle into new homes that suit their new working arrangements.

Apartment List has surveyed workers multiple times over the course of the pandemic, as telework shifted from a temporary stop-gap measure to curb the spread of COVID-19 into an established workplace norm. Our surveys capture not only who is working remote versus on-site, but how different groups are approaching their future job and housing situations. In our latest survey, we identify a gradual shift towards hybrid working arrangements (i.e., some days at home, some days on site) but less enthusiasm from younger workers about the remote economy.

Remote work is still (and will remain) common

Our team conducted surveys in April and December 2021.1 In both, we asked employed adults how frequently they work from home rather than a physical jobsite like an office or a storefront. In the analysis that follows, we consider someone a remote worker if they spend at least half their time working from home.

Remote work declined in popularity throughout 2021, but only marginally. Last April, 51 percent of workers were working from home at least half the time, and by December, that share had fallen to 44 percent. And within this remote group, we observed a shift from working only-at-home to working mostly-at home. 56 percent of remote workers were exclusively at-home in April, compared to 47 percent in December. Hybrid arrangements that include on-site work days have become more common, but broadly speaking, remote work continues to entrench itself in the national economy. Positive business outcomes, coupled with the persistent uncertainty of the pandemic, have made it challenging to entice (or force) remote-capable employees to return to the office.

While a crop of workers made their way back to the office in 2021, for those who remained remote, their expectations for the future did not budge. We asked workers if their employer signaled that their jobs would continue remote or transition back to the office post-pandemic. In April, 77 percent said that according to their employer, remote work would continue indefinitely. In December, 78 percent said the same. And again we see hybrid arrangements gaining some popularity.

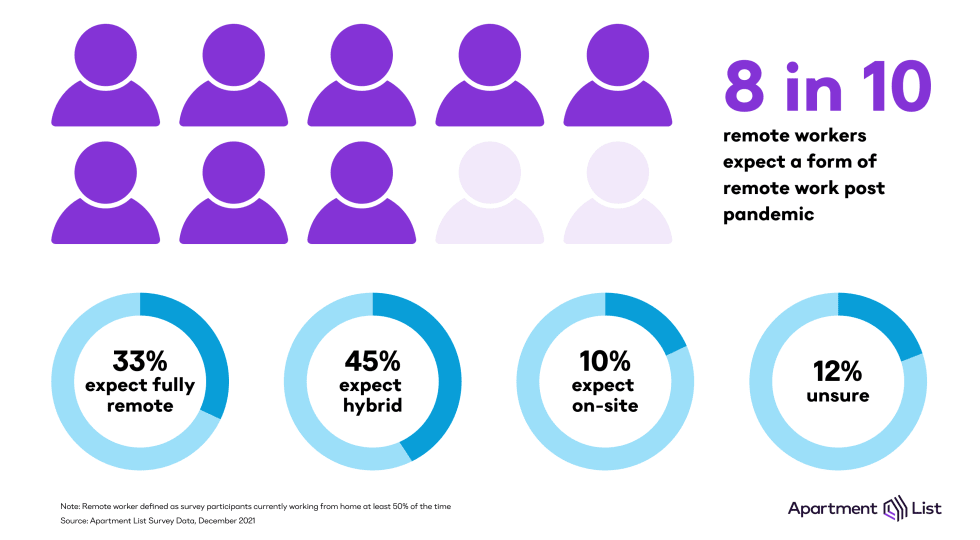

Again we see hybrid arrangements gaining some popularity. Last April, 40 percent of remote workers expected their employers to adopt remote work permanently, compared to 37 percent who expected hybrid work to become the norm. In December, the share expecting full-time remote work from home fell to 33 percent while the share expecting hybrid remote work rose to 45 percent.

But not everyone is sold on the remote work revolution

While certain occupations lend themselves to remote work more easily than others, our survey finds that telework remains common for workers of all ages. As of December 2021, millennials are the most-remote generation, but by only a few percentage points compared to the rest. Across the board, more than 40 percent of workers in all generations are working from home, from Boomers nearing the end of their careers to Gen Zers who are just starting theirs.2

But not everyone is enthusiastic about remote work becoming the norm in the post-pandemic economy. It has its obvious pros and cons, most notably a healthier work/life balance coming at the expense of feeling less connected to co-workers, according to one study. But not everyone weighs these competing effects in the same way at different stages of their careers. Our survey finds that more than any other generation, 62 percent of Boomer remote workers believe working from home is “extremely desirable” going forward. 54 percent of remote workers from Generation X agree, as do just over half of all Millennial remote workers. Generation Z is the only group in which a majority of workers feel differently; among this youngest batch of remote workers who were ages 25 or younger at the time of our survey, 36 percent said remote work is “extremely” desirable, 27 percent described it as “very” desirable, 28 percent as “somewhat” desirable, and the remaining 9 percent as “not so” or “not at all” desirable.

Gen Z’s skepticism of remote work is consistent with earlier research by our team and suggests that the benefits of remote work get more salient as one progresses past the initial stages of their career. For older generations, the remote work revolution offers a welcome respite from decades of worsening commutes, and in return, more time for non-work priorities. But Gen Z workers, many of whom already had their college experiences stunted by the pandemic, are less enthusiastic about also beginning their careers remotely. Doing so restricts the social aspects of a job and makes it more challenging to network and gain exposure to a broad swath of colleagues.

What does this all mean for the housing market?

Historically, housing and labor markets were tightly linked. Popular housing markets were the ones that offered easy access to business districts, and their rent prices were high because of it. But in 2020, remote work began severing this linkage, as millions lost their jobs and millions more transitioned to full-time remote work. Newcomers flooded once-quiet cities, putting strain on local housing supply. As a result, prices cratered in large metropolitan cities and rose in smaller ones.

But as described in our survey, the growing popularity of hybrid remote work is beginning to repair the threads that connect homes and jobs. Hybrid work is significantly more restrictive than full-time remote work when it comes to workers’ abilities to relocate. The latter gives workers the flexibility to live anywhere with an internet connection, whereas the former limits workers to a fairly narrow radius around their job site. If remote workers must endure commutes only a couple times per week, they could expand the commuting zones of major metropolitan areas, but long-distance cross-metro moves will generally not be feasible. Throughout 2021, as hybrid arrangements were becoming more common, we saw rent prices picking back everywhere, in urban and suburban markets alike.

Dense urban cities have had the most volatile housing markets over the past two years, and while some are still recovering economically from the pandemic, the once-predicted “death of cities” turned out to be a gross exaggeration. Low apartment vacancy rates and surging rent growth signal that cities are popular destinations once again, even in a remote economy. Generation Z workers are a big reason for this. They were the most mobile generation last year,3 and being less satisfied with remote work than older generations, they are enticed by the urban amenities that cities have to offer outside the home office. Gen Z is taking advantage of the residential flexibility offered by remote work, but not necessarily to move to the suburbs nor abandon the big cities that cater to them.

But as we learned from our survey, preferences shift with age. So as Gen Z workers get older, get married, and start families, their attitudes towards remote work may soften and their preferences for housing may change. But for now, it looks like more employers will be adopting hybrid work environments that have something to offer everyone.

- Surveys were administered through SurveyMonkey Audience and collected on April 9-10, 2021 and December 16-17, 2021. Each survey captured responses from approximately 5,000 employed workers, a sample that is representative of the U.S. population in terms of gender and age.↩

- Generations are defined using the birth year of the respondent and are consistent with definitely from the Pew Research Center. Baby boomers were born 1946-1964, gen Xers were born 1965-1980, millennials were born 1981-1996, and gen Zers were born 1997 or later.↩

- The 1-year mover rate among ages 20-24 was 18%, substantially higher than older generations. Source: US Census Bureau, Geographic Mobility: 2020-2021, Table 6.↩

Share this Article