The Housing Affordability Struggle of 21st Century Veterans

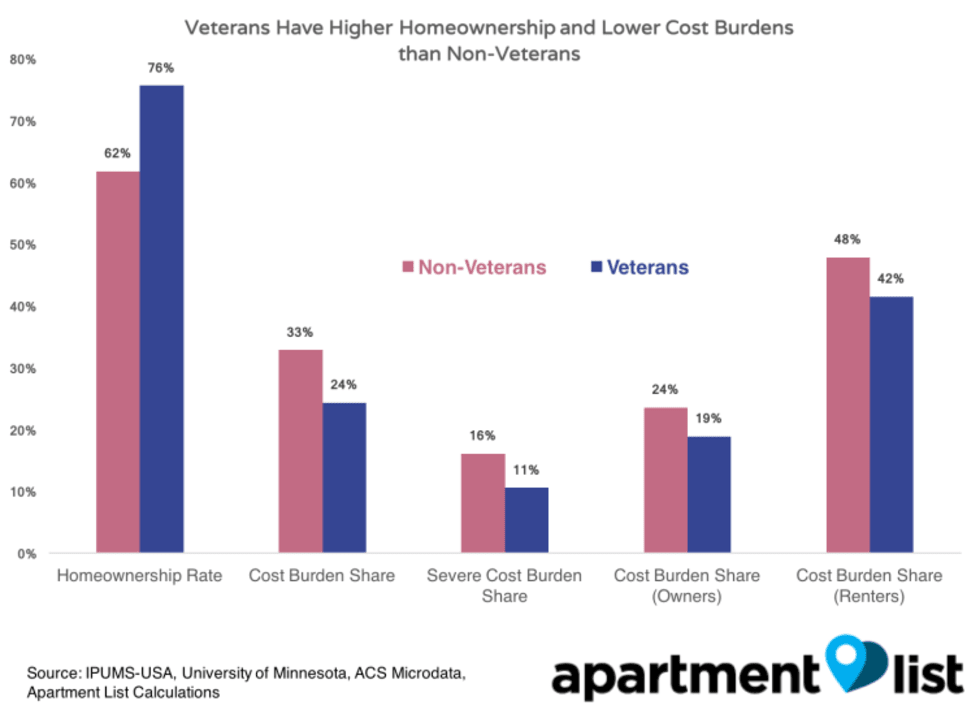

- On average, veterans have higher homeownership rates (76% vs. 62%) and lower housing cost burdens than non-veterans (24% vs. 33%). But these averages mask a troubling trend.

- Post 9/11 veterans have become the first and only generation of veterans to struggle with housing affordability compared to civilians of like ages and demographics.

- Post 9/11 veterans are nearly 5% less likely than comparable non-veterans to be able to afford their housing costs, even when controlling for age, race, gender, and location. Gulf War and Vietnam veterans, on the other hand, are 25% and 10% more likely, respectively, to afford their housing costs.

Download Complete National and Local Data

Over twenty million U.S. military veterans live in America, comprising just over 7% of the adult population.1 While this share has been declining, new veterans are coming home each year. In 2016, the number of men and women serving in wars throughout the Middle East over the past twenty-five years finally surpassed the number of Vietnam veterans. As these troops return home, they face unique challenges re-entering labor and housing markets. As these markets continue to evolve, are our policy efforts adequately supporting them?

With Veterans Day approaching, we stop to take stock of how veterans are faring in today’s housing market. We find that the answer depends entirely on the generation of veterans in question. Older generations of veterans are doing quite well, with very high homeownership rates and low likelihoods of housing cost burdens. Those serving after 9/11, however, appear to be uniquely disadvantaged. They have become the first generation to return from combat and struggle with housing affordability more than their civilian counterparts.

In Aggregate, Veterans Appear to Fare Well in Housing Markets

On first glance, veterans outperform non-veterans on key housing market statistics. Veterans are more likely to own their home than non-veterans. Today, 76% of veteran households own their homes, compared to just 62% of non-veteran households.2

Veterans are also less likely to be housing cost burdened.3 Nearly a third of non-veterans pay more than the recommended standard of thirty percent of income.4 Veterans fare far better on affordability; fewer than a quarter of veterans cannot afford their housing. Veteran households are also over thirty percent less likely to be severely cost burdened (spending more than half of income on housing cost) than their civilian counterparts.

We see this average veteran affordability premium in both owner-occupied and rental housing. Moreover, higher average veteran homeownership rates and lower cost burdens hold even when controlling for head of household age and demographics.5

This comparison is good news for veterans and perhaps should not come as a surprise. Ensuring that veterans succeed in the housing market upon their return is a federal policy priority. Veterans are eligible for VA loans, which are government-backed mortgage products that require no down payment up to a certain market-specific cap. Veterans have long been a targeted demographic in the fight against homelessness, and a variety of housing allowances for veterans furthering their education have been written into GI Bills. These aggregate statistics show that these policies are sufficient to keep the average veteran from falling behind in today’s housing market.

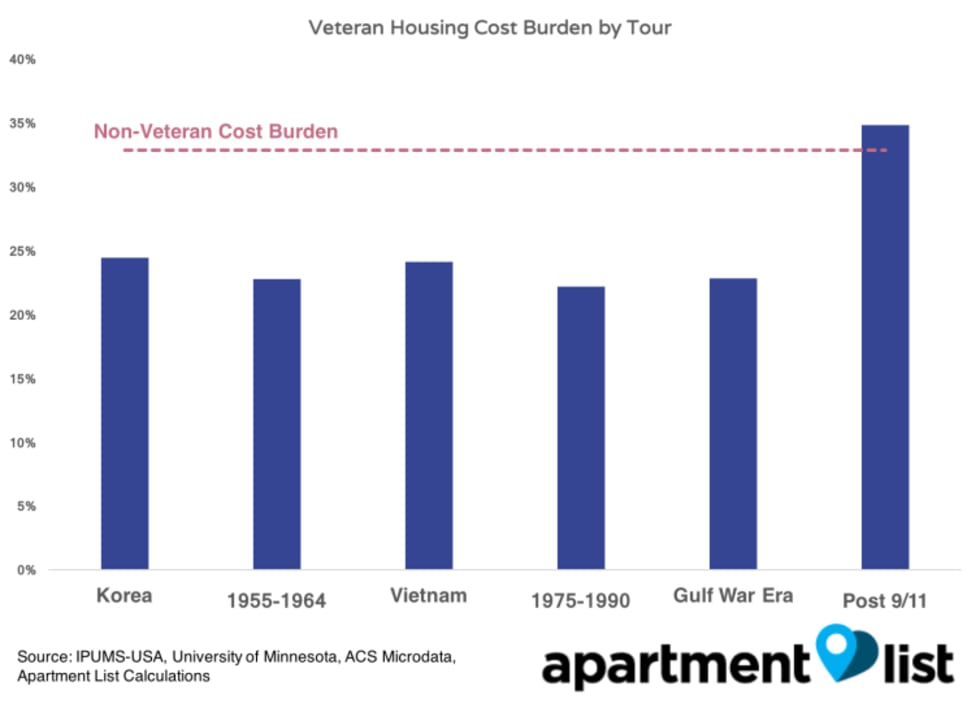

Post 9/11 Veterans, However, Struggle with Affordability and Homeownership

When we take a closer look at disaggregated veteran data, we unearth a troubling trend. Veterans that served in the Post 9/11 Era actually have astonishingly high cost burdens compared to prior generations with military service. Across veteran generations from all previous tours of service -- from the Korean War to the Gulf War -- cost burden rates are below 25%. Nearly 35% of post 9/11 veterans, however, are cost burdened. These young veterans, in fact, are more likely than the average civilian to struggle with housing affordability.

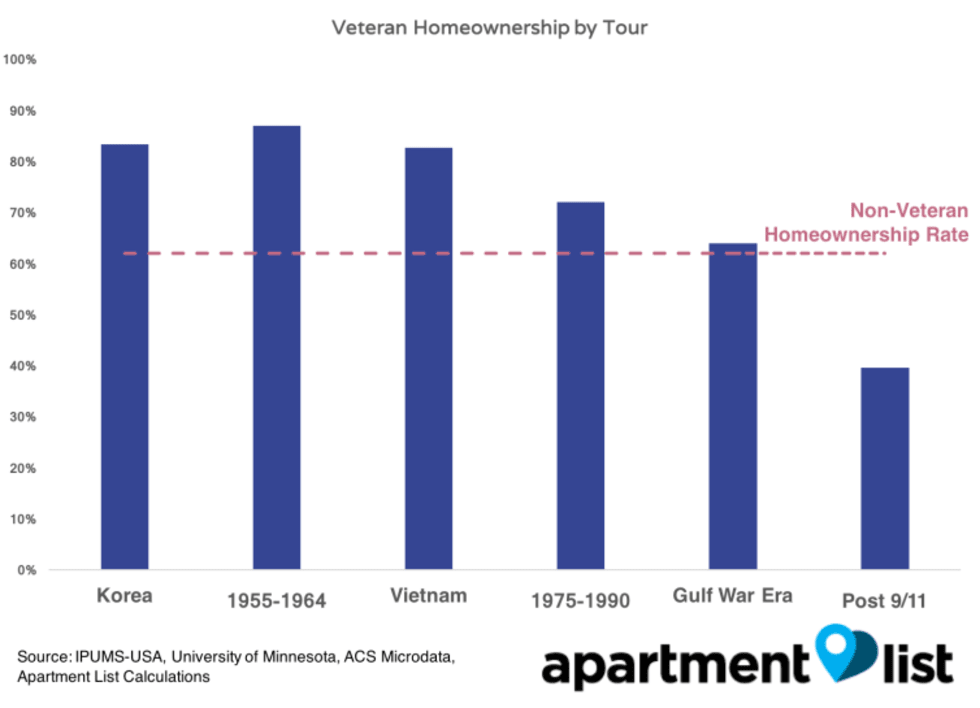

Trends in veteran homeownership show a similar pattern. Veterans who served in the 21st century are far less likely than prior veteran generations to own their home. Despite having broad access to zero-down mortgages with favorable rates through the VA loan program, fewer than half of post 9/11 veterans own their home.

These differences could reflect unique challenges faced by a new generation of veterans, or alternatively, they could be driven by changing demographics over time. Obviously, veterans who served more recently are, on average, younger, and younger households are less likely to be homeowners. The post 9/11 veteran generation is also the most diverse in U.S. military history. As more underrepresented minorities serve in the military, veteran cohorts become more exposed to a variety of new challenges, such as the lasting effects of racial segregation. This begs the question, can changing demographics explain the post 9/11 veteran housing affordability struggle?

This Concerning Trend Holds When Controlling for Demographics

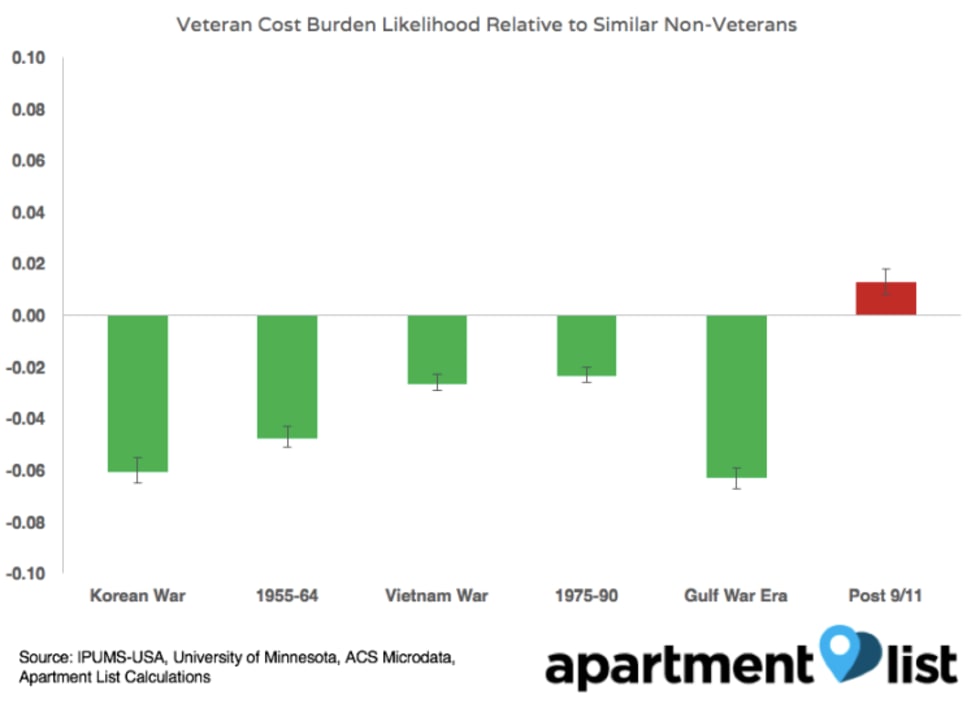

We design a regression model to understand whether post 9/11 veterans’ affordability struggle is driven by demographics.6 This model allows us to compare housing market outcomes for veterans and demographically similar non-veterans in the U.S. With this analysis, we can answer the question, “How do veterans fare in the housing market compared to non-veterans, controlling for age, gender, and race?”

We re-examine the analysis of veteran cost burdens with this framework and plot the resulting veteran effects. These can be interpreted as the estimated increase (or decrease) in the likelihood of veterans in this generation being cost burdened relative to civilians of the exact same age, race, and gender.

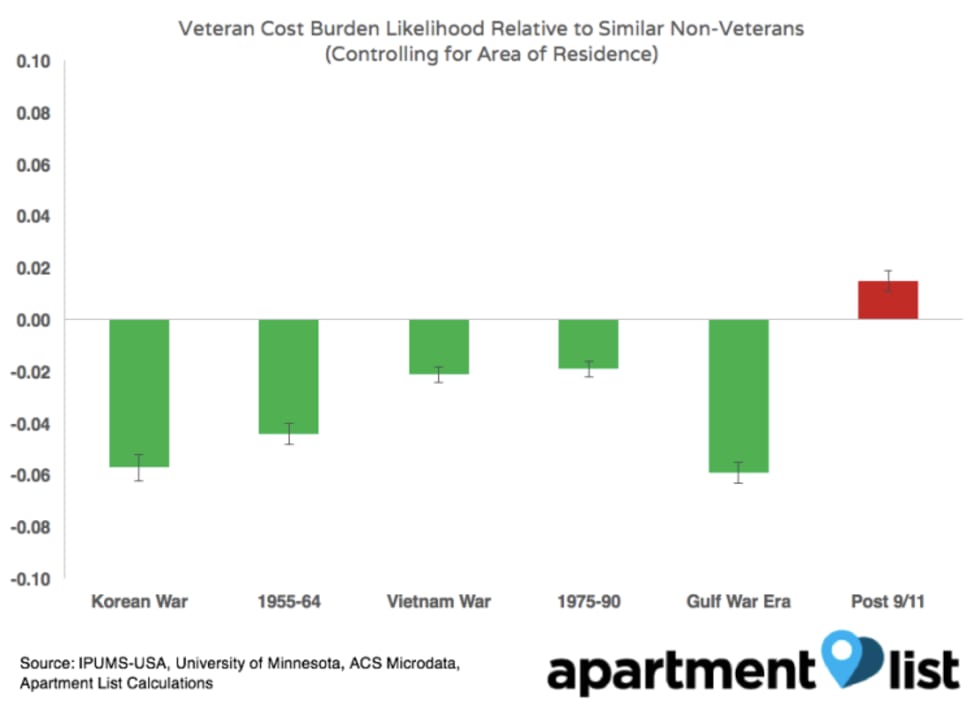

Even controlling for demographic changes over time, post 9/11 veterans are still the only generation of veterans who struggle with housing affordability more than their civilian counterparts. This difference is statistically significant and a large swing from the advantage that prior generations of veterans enjoy. In percentage terms, Vietnam veterans are 10% more likely than civilian peers to be able to afford their housing costs. Gulf War veterans are 25% more likely than civilian peers to be able to afford their housing costs. Post 9/11 veterans are 5% less likely than comparable non-veterans to be able to afford their housing costs.

The lower homeownership rates among post 9/11 veterans, on the other hand, are explained by demographic composition. Post 9/11 veterans are not any more or less likely to own a home than civilians of the same age and race, though previous generations of veterans did enjoy a homeownership premium over non-veterans. This finding yields two implications. First, policy wishing to support veteran homeownership in the 21st century should account for the unique challenges that underrepresented minorities face in housing markets. Second, post 9/11 veterans’ struggle to find affordable housing is not driven by the fact that more young veterans are being pushed into or out of the rental market.

Previous Veteran Generations Were Not Similarly Disadvantaged When Younger

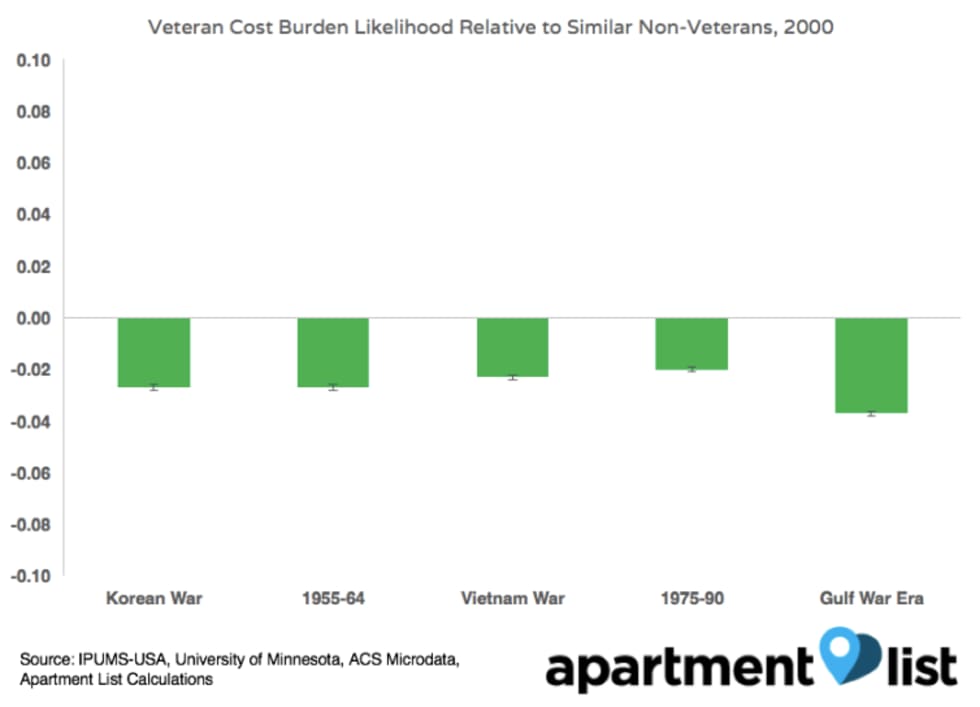

The disadvantage that young veterans face in the housing market reflects a new trend. Prior wartime veteran cohorts enjoyed an affordability advantage in their younger years as well. When we estimate how veteran cohorts fared on housing affordability relative to their peers in 2000 (again controlling for demographics), we find that all cohorts enjoyed an affordability advantage. Gulf War veterans, who were the youngest cohort in 2000, were significantly less burdened by housing costs than their civilian counterparts.

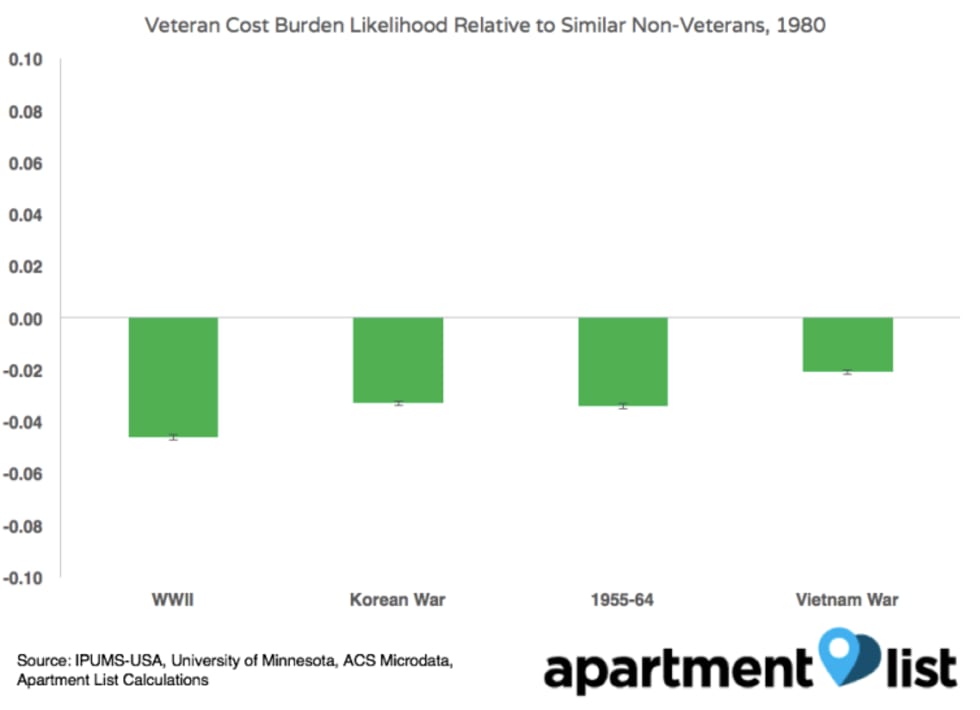

Moving further back in time, all working-age generations of veterans outperformed their peers in the 1980 U.S. housing market. Five years after the end of the Vietnam War, young Vietnam veterans were more than two percentage points (six percent) less likely than comparable non-veterans to have rents or mortgages eat up more than thirty percent of their paycheck.

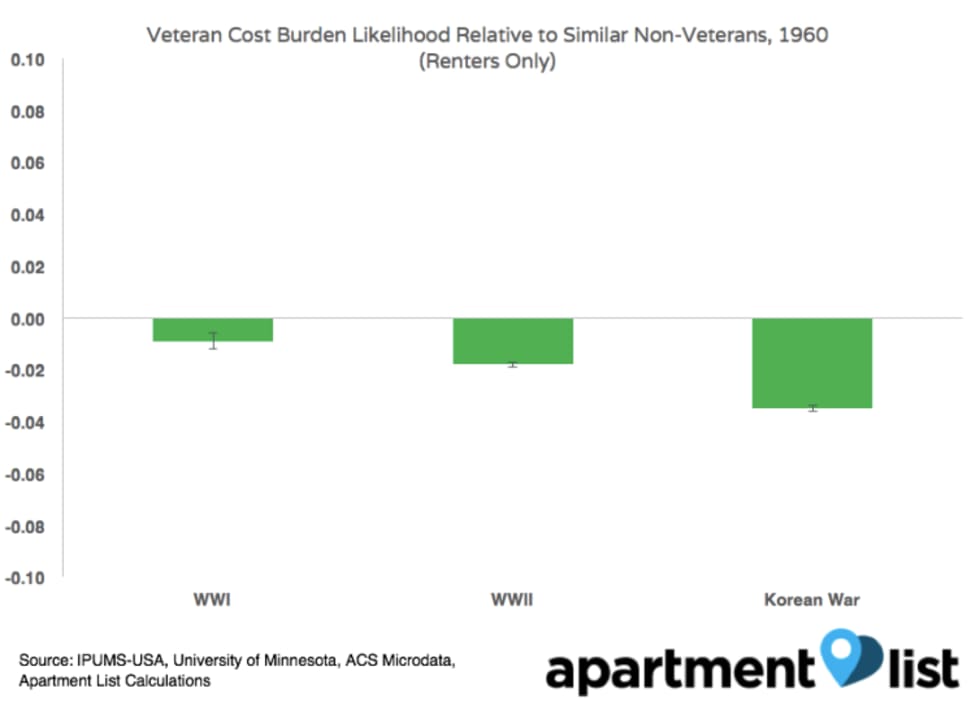

Data from the 1960 only allows for a comparable study of the renter population. Nevertheless, in 1960, WWI, WWII, and Korean War veteran cohorts were all less likely than non-veterans with identical demographics to be cost burdened. In fact, in 1960, younger veterans held a greater affordability premium over non-veterans.

Long story short, young veterans have not always been at a disadvantage in the housing market. The veterans returning from war today are part of the first generation to not enjoy a housing affordability advantage.

What is Driving This New Veteran Generation’s Adverse Housing Outcomes?

What explains post 9/11 veterans' unique battle with housing affordability? We test three natural explanations.

First, post 9/11 veterans may struggle with affordability simply because they earn lower incomes than non-veterans but vie for the same housing. We find that this is not the case. 21st century veterans are not disproportionately struggling in the labor market. Controlling for age, race, and gender, we find that post 9/11 veteran households actually earn nine percent more non-veterans.

Second, the new generation of veterans may be supporting relatively larger households. Our analysis finds that this is also not the case. post 9/11 veterans support the same number of people in their household, on average, as like non-veterans.

Finally, we explore whether 21st century veterans struggle with affordability because they choose to live in relatively more expensive places. Younger veterans, for example, are less likely than older cohorts to live in rural areas. Could this preference account for the disappearing housing affordability?

To test this hypothesis, we re-run our primary analysis controlling for area of residence.7 That is, are veterans of different eras more of less likely that non-veterans of the same age, race, and gender living in the same area to be cost burdened? The answer is no. In fact, our estimates change very little. Moreover, we find that employed veterans of all generations have comparable commute times to non-veterans.8 Even controlling for location choice, post 9/11 veterans are more cost burdened than peer civilians today.

Moving Forward

So where does this leave us? We hypothesize that 21st century veterans struggle with housing affordability due to unique challenges that lagging policy has failed to address. For one, many post 9/11 veterans returned home during either the build up to or recovery from the 2008 housing market crash. This coincidence was historically bad timing. In the buildup to the crisis, low down payment mortgage loans flowed freely to the general population, so perhaps the advantage of VA loans was not as significant during this period. In the aftermath, veterans may have been disproportionately affected by tight credit and market volatility at a time when they would have been settling down. To add fuel to the fire, the rise of the for profit college sector and opioid crisis may have targeted young veterans in the past ten years.

We believe more research is needed to get to the root of the issue and allow policy to adjust. Most programs that support veterans in the housing market takes place either on the margin of homeownership or the margin of homelessness. Increasingly, middle-income renting veterans that are not close to either margin may need support as well. With veterans becoming a smaller and smaller share of the population, their benefits and experiences become less commonplace and understood, even during prolonged periods of combat. As young adults start to enlist that were not even born before the 9/11 attacks, we need to feel the urgency of finding 21st century solutions to the problems of 21st century veterans.

Download Complete National and Local Data

- American Community Survey, 2017 1-Year Estimates.↩

- We define a veteran household as one where the designated head of the household is a veteran.↩

- We use the standard definition of housing cost burden, which is an indicator for whether or not a household spends more than thirty percent of its income on housing costs.↩

- We use the terms “cost burdened” and “not affording housing” interchangeably in this report, though we acknowledge that the traditional thirty percent metric is not a perfect definition of affordability.↩

- In a regression analysis where we control for age and race, though a series of fixed effects for each age and race (not interacted), we find veteran status is positively correlated with homeownership and negatively correlated with both cost burden and severe cost burden.↩

- We run ordinary least squares regressions predicting cost burden with fixed effects for each tour of duty, each age, each race in the ACS microdata, and gender. The plotted estimates below are the resulting coefficients on the relevant tour of duty indicators.↩

- For this analysis, we define an area as a PUMA (which is the finest geography available in the American Community Survey Microdata). The results also hold if we control for metropolitan area, which is a coarser geography.↩

- Employed post 9/11 veterans have an average commute time of twenty-five minutes, just like the average employed American.↩

Share this Article